Outside Westminster Abbey

As the class was guided through Westminster Abbey in London, I was overwhelmed by the sheer volume of burials and memorials of historically significant figures we were presented with. From Isaac Newton, to Charles Dickens, to over a dozen English and Scottish monarchs, Westminster Abbey is the place to be buried if you were an important person. This was just one of the many places of burial for monarchs and historical figures that we’ve visited in the duration of this class. Visiting all of these memorials sparks plenty of thinking about how we should remember historical figures, and how memorials and burials can influence someone's public memory after they’re gone.

One of the most interesting details from our tour of Westminster Abbey was the explanation of the coffins of Elizabeth I and Mary I, commonly referred to as “Bloody Mary” due to the hundreds of executions she ordered during her reign as Queen. The sisters had a complicated relationship due to political and religious differences. When Elizabeth died, nearly 50 years after Mary, her coffin was placed on top of Mary’s, with a monument above the coffins that features a sculpture only of Elizabeth. Our tour guide told us how much Mary would have despised sharing a coffin with Elizabeth, being placed below her, and not being memorialized in the same way.

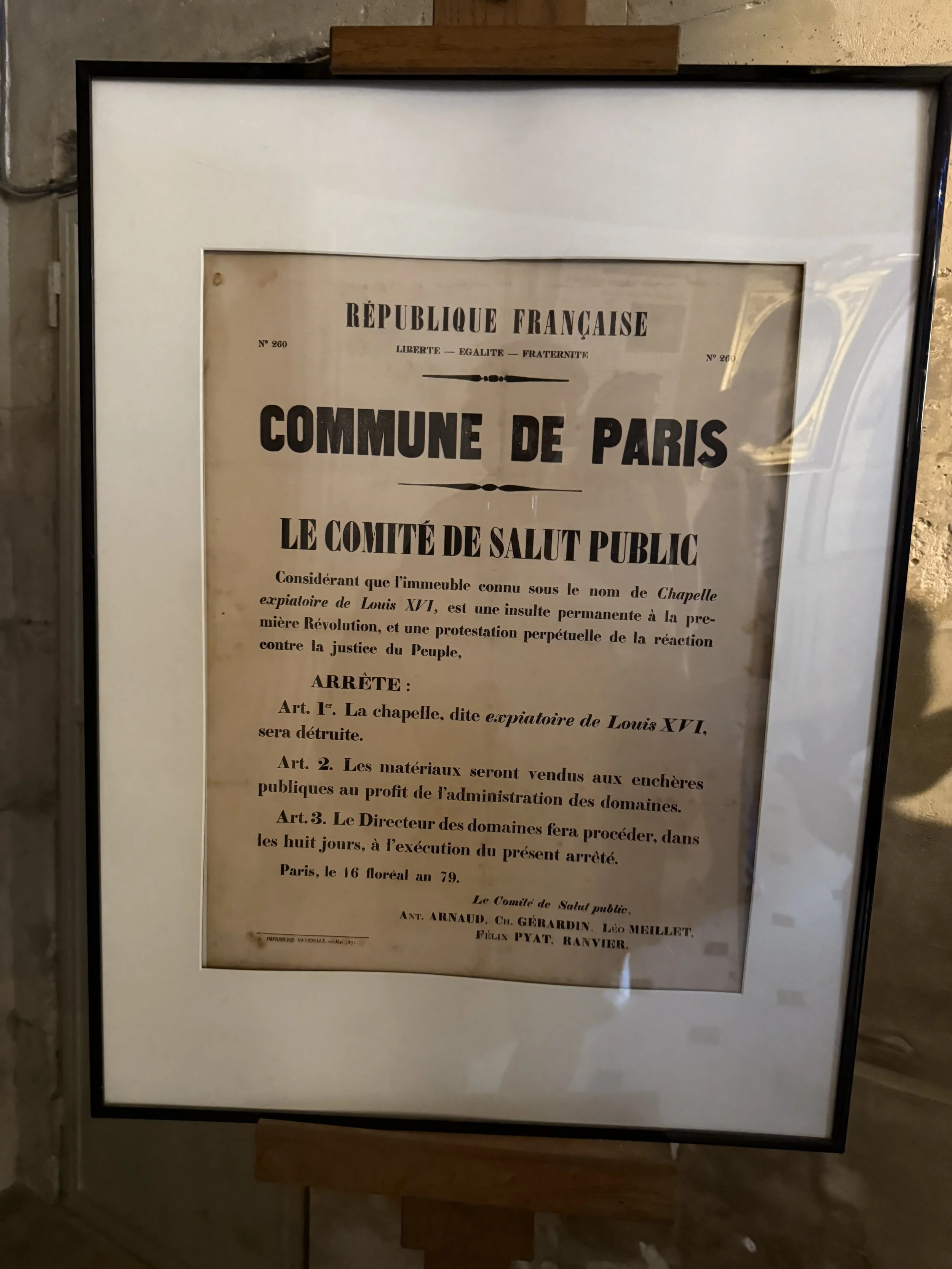

Fast forward to our time in Paris, when we visited the Chapelle Expiatoire, a chapel built by Louis XVIII to commemorate the memory of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. While walking through the modest but beautiful chapel and admired the quite well-done statues of the two figures, I couldn't help but feel a bit strange about the whole thing. A chapel built entirely to honor these two representations of the opulence and incompetence of the monarchy, built in a post-revolution France. On one hand, it’s important to recognize and honor history, but should these figures have been memorialized to this extent? There is a poster framed and on display in the chapel written by the Paris Commune demanding the destruction of the chapel. Of course, the chapel itself is now an important and interesting piece of history that should be preserved, but I think I probably would have agreed with the sentiments of the poster if I was around at that time.

Poster in protest of the Chapelle Expiatoire

My slight discomfort with this experience didn’t hold a candle to how I felt while walking through the Charles Dickens Museum in London. Five floors of carefully arranged recreations of what the house may have looked like when Dickens lived in it, filled with personal belongings and in-depth details about Dickens’s life. There were authentic letters about Dickens’s separation from his wife, theories about his possible secret relationship with his sister-in-law, and even a preserved lock of Dickens’s hair. This visit really got me thinking about how I would like to be remembered after I pass, and how I would feel to be in Dickens’s position. If I was a famous novelist, I would want to be remembered by the public for the work I produced, and that alone. Even though he lived two centuries ago, what right do we have to be digging through his personal belongings and reading letters he wrote about his failing relationship? I’m interested in Dickens as an author, and I’m interested in how his personal life could have influenced his writing, but it didn’t feel quite right to view all of his personal belongings and letters on display in his home. Maybe I just don’t understand the appeal.

This whole idea of how we remember people after death relates quite directly to the texts we’ve been reading. How would Charles Darnay have been remembered? Would he have been known as a traitor to the revolution, a representation of the evil acts of the Evrémonde family? Would he have heard these things as he was in hiding after narrowly avoiding death? How would Sydney Carton have been remembered? After a life of not living up to the potential he knew he had, he heroically sacrificed his life for Darnay’s. Would he have been remembered by his missed potential, would he be remembered at all? Carton’s heroic actions were worthy of a spot in Westminster Abbey, but he was likely forgotten after death by anyone other than the select few who were aware of his sacrifice.

There’s one question I keep coming back to as I write this: Does it really matter how we’re honored after death? We will be dead, after all. We won’t know any better. Those who knew us will remember us for who we were, and maybe that’s enough. As we were waiting to enter the beautiful and extravagant tomb of Napoleon, my classmates and I spoke about what we’d like to have done with our remains when we die. It was a fun and oddly touching conversation that touched on this recurring theme of remembrance.

Outside Napoleon’s Tomb