When I stepped into the Maison de Victor Hugo, I wasn’t just walking into a preserved home; I felt as if I had entered the intimate space of a man who carried entire worlds inside his head. The rooms were warm and slightly dim, the kind of lighting that makes you lower your voice instinctively. Ornate furniture, patterned wallpaper, and personal objects gave the space a lived-in quality, even though Hugo hadn’t been here in over a century. Among his bedrooms and handwritten notes, the painting of Jean Valjean walking beside young Cosette as she carried her water bucket caught my eye. The moment it captured was quiet, almost ordinary, yet pivotal in both their lives.

Painting of Jean Valjean and Cosette

In Les Misérables, Cosette’s childhood is defined by fear, deprivation, and invisibility. Under the care of the Thénardiers, she is overworked and underfed, treated more like a servant than a child. The scene in the painting, drawn from the moment Valjean meets her when she fetches water at Madame Thénardier’s demand, radiates a tenderness that feels almost miraculous in contrast. He walks beside her, step for step. That placement says everything: I am here. You are safe. Standing before it, I realized Hugo wasn’t just telling a story about revolution and justice; he was also exploring the quiet revolutions sparked by compassion, protection, and dignity. Valjean changes Cosette’s future by being the first to show her love, and she gives him a new purpose. This delicate balance of power and tenderness is what makes their relationship so compelling, a reminder that even small acts of kindness can be revolutionary in a harsh world.

““Compassion and tolerance are not a sign of weakness, but a sign of strength.” ”

Leaving the Maison de Victor Hugo, we headed to the Musée Carnavalet. The streets felt alive with history, the sounds of distant conversations, the faint scent of freshly baked bread drifting from a nearby boulangerie, and the chatter of footsteps on cobblestones worn smooth by centuries of travelers.

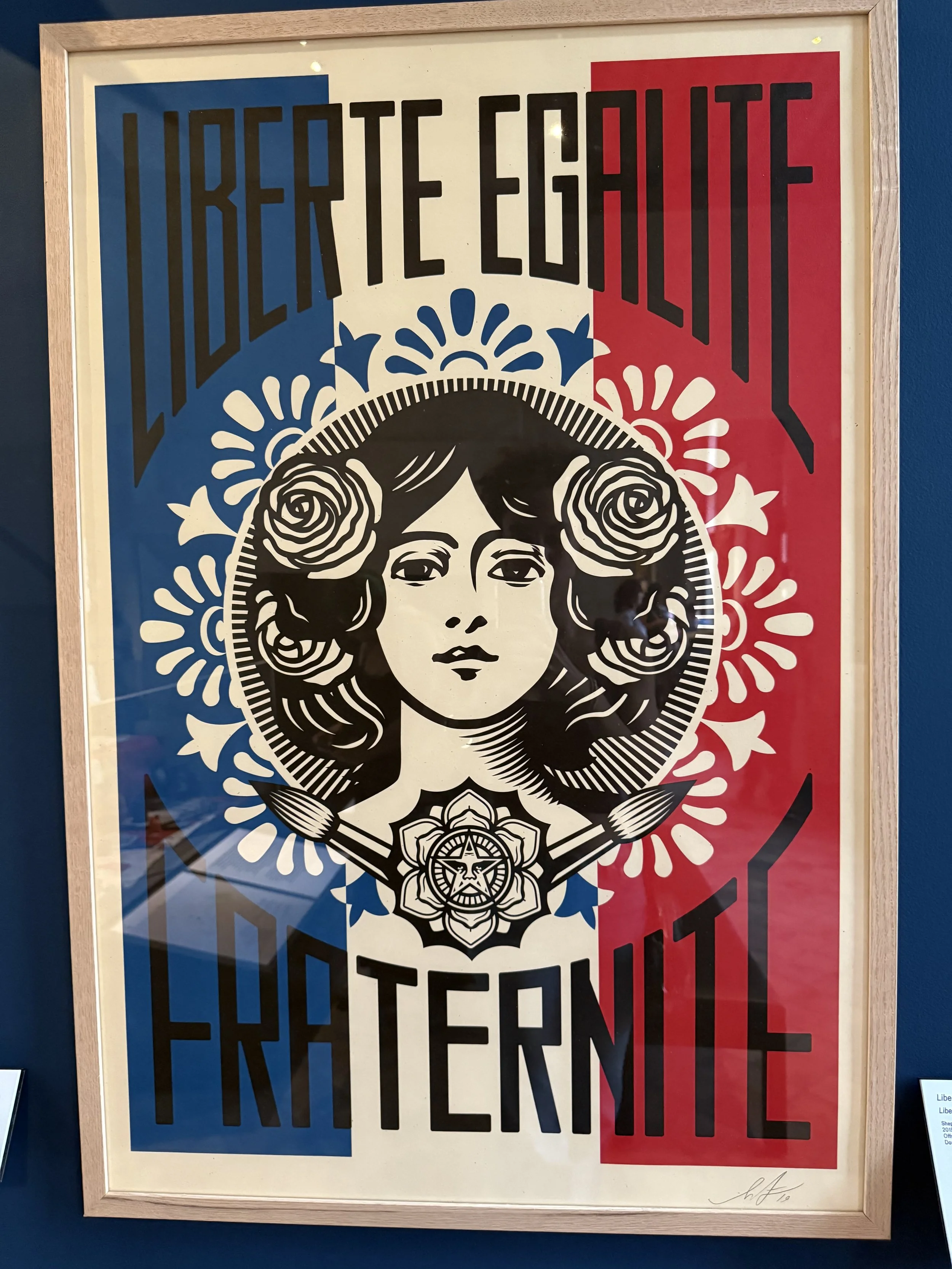

Inside, the museum unfolded like a labyrinth, each room brimming with paintings, artifacts, and everyday objects that told the story of Paris across centuries. Shepard Fairey’s Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité immediately caught my eye. Its bold colors and powerful message vibrated against the muted tones of the surrounding galleries, pulling me into the revolutionary spirit of Les Misérables, especially the passion of the student-led ABC group fighting the monarchy. I’d noticed this same motto engraved on buildings throughout the city, most memorably at the Palais de Justice, a reminder that liberty, equality, and fraternity remain values deeply woven into French culture.

Shepard Fairey’s Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité

But the part of the Carnavalet that truly stopped me was something I hadn’t expected: a section dedicated to Black Parisians in the nineteenth century. I was surprised, not because I didn’t know such communities existed, but because their stories are so rarely given space in major museums. The weight of that omission felt somber.

Further inside, portraits of artists and intellectuals sat alongside documents recording the lives of formerly enslaved individuals who settled in Paris. Their presence disrupted the common image of nineteenth-century Paris as entirely white, prompting me to reconsider the incomplete history I’d absorbed. One painting, Au Nègre joyeux (The Joyful Black Man), had been used to advertise food products imported from the colonies, reinforcing the stereotype of the cheerful Black servant.

I was struck by how many of these stories echoed themes from Les Misérables: migration, survival, and the fight for dignity in a society that often resisted their presence. Jean Valjean’s struggle to redefine himself after prison mirrors the battles these individuals faced to claim their place in a society that did not fully recognize them. Both are stories about navigating exclusion and injustice. Standing in that room, I thought about how history is shaped as much by what’s left out as by what’s included. For every celebrated figure we remember, countless others are lost to time, often because they didn’t fit the dominant narrative. Seeing these Black Parisians represented, however briefly, was a reminder of the gaps in collective memory and the ongoing work to fill them.

As I made my way back through the museum, I realized my visits to the Maison de Victor Hugo and the Musée Carnavalet were connected in ways I hadn’t anticipated. Hugo’s Paris in Les Misérables is a tapestry woven from voices on the margins: the poor, the criminalized, the forgotten. The Carnavalet’s glimpse into nineteenth-century Black Parisians felt like discovering another missing thread in that tapestry.

Walking back through the streets that afternoon, I felt the city’s layers pressing in on me. Paris is often romanticized as a city of lights and beauty. Still, it is also a city of hidden histories, quiet resistance, and everyday people whose lives shaped the city as much as any king or general. The same streets that echoed with Valjean’s footsteps also carried men and women living outside the center of the story, yet whose stories quietly shape the soul of Paris. As I passed small cafés and bustling markets, I thought about how the present city holds so many stories at once, stories of privilege and struggle, celebration and sorrow. It made me realize that the real revolution is the ongoing work of remembering and honoring all of these voices, not just the loudest or most powerful.

Au Nègre joyeux

Travel often promises novelty, but for me, the most rewarding moments are when the past feels suddenly close, not as a foreign country, but as a set of human experiences that still matter. Whether it’s a fictional girl finding safety with someone who loves her, or a real person carving out a life in a society that wasn’t built to welcome them, these are stories worth holding onto.

In the footsteps of Jean Valjean and Cosette, I see how simple acts of care become quiet rebellions against a world that too often forgets. I’ll remember that painting of them walking together, step for step, and I’ll think of the other pairs who must have walked these streets—fathers and daughters, friends, strangers—bound together by the simple, radical act of care. And I’ll remember that telling their stories isn’t just about honoring the past; it’s about shaping the present and imagining a future where those stories are never lost again.