“Medicine, law, business, engineering, these are all noble pursuits, and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

Robin Williams delivers this line in one of my favorite films, Dead Poets Society. As someone studying both medicine and engineering, I make it a priority to seek out beauty wherever I can. To eagerly read, to love art, people, and places deeply, and to stay curious. Growing up in St. Louis, my mom and I took full advantage of the city's free cultural institutions, including the art museum, zoo, and science center. Lately, the St. Louis art museum has felt like the perfect escape (pictured below). So when I had the opportunity to visit the Louvre, I was practically kicking my feet with joy.

Visiting the world's largest museum can be overwhelming if you are trying to see everything, nearly impossible in a day. Mathematically, you'd need to absorb one artwork per second. Instead, I was given a challenge (boy, do I love challenges) to find characters of Les Misérables in the art.

Walking into the Louvre, the Mona Lisa felt more like a box to check off than a personal destination. It's a small, subdued portrait of a rather ordinary woman. Painted in 1503, she lived in quiet and secluded French Palaces until the Revolution, then Napoleon's bedroom, and finally the Louvre. But it wasn't until her mysterious disappearance in 1911 that she became famous. For two years, crowds visited the space where she once hung. When she returned, she was no longer just a painting; she was a natural treasure and cultural icon.

This transformation mirrors Cosette's journey in Les Misérables. When Marius first walks past her, she is a quiet, "rather sullen" girl in a garden. Six months later, he notices a shift: "no longer the ingenuous and uncomplicated gaze of a child, it was a mysterious chasm that had opened up, then abruptly closed again." The next day, Marius puts on his new hat and boots to impress her. He seems to fall for what she represents, rather than who she is.

Just like the Mona Lisa, Cosette is admired less for her true self and more for what others project onto her—some symbol of mystery. Once disregarded by the Thenardiers and seen only by Valjean, she eventually becomes distant, idolized, and romanticized. Marius, like the crowds who once visited the empty wall where the Mona Lisa used to hang, falls for the idea of her. Both Cosette and the Mona Lisa are framed by distance and desire.

There's also the question of identity. For centuries, historians have speculated about the identity of the Mona Lisa. Lisa Gherardini? But no commission from her husband exists. A fantasy? Da Vinci himself in disguise? Similarly, Cosette grows up in the shadow of an untold past. She doesn't learn her mother's name, Fantine, until Valjean's final moments. It makes me wonder, if we knew the Mona Lisa's origins, would she seem a little less mysterious?

Leaving the Mona Lisa behind, I wandered down the stairs and found myself face to face with Michelangelo's Rebellious Slave. I noticed how his potent torso strains every muscle and ligament to break free from the bands that confine him.

It was a younger Valjean, carved in stone.

Valjean spends his entire life trying to break free from the identity of "convict", from society's labels, from Javert's pursuit, even from his guilt. No matter how far he runs or how deeply he changes, the chains remain. Like the statue, he is both powerful and imprisoned. Both represent the systemic barriers that keep their souls from being free.

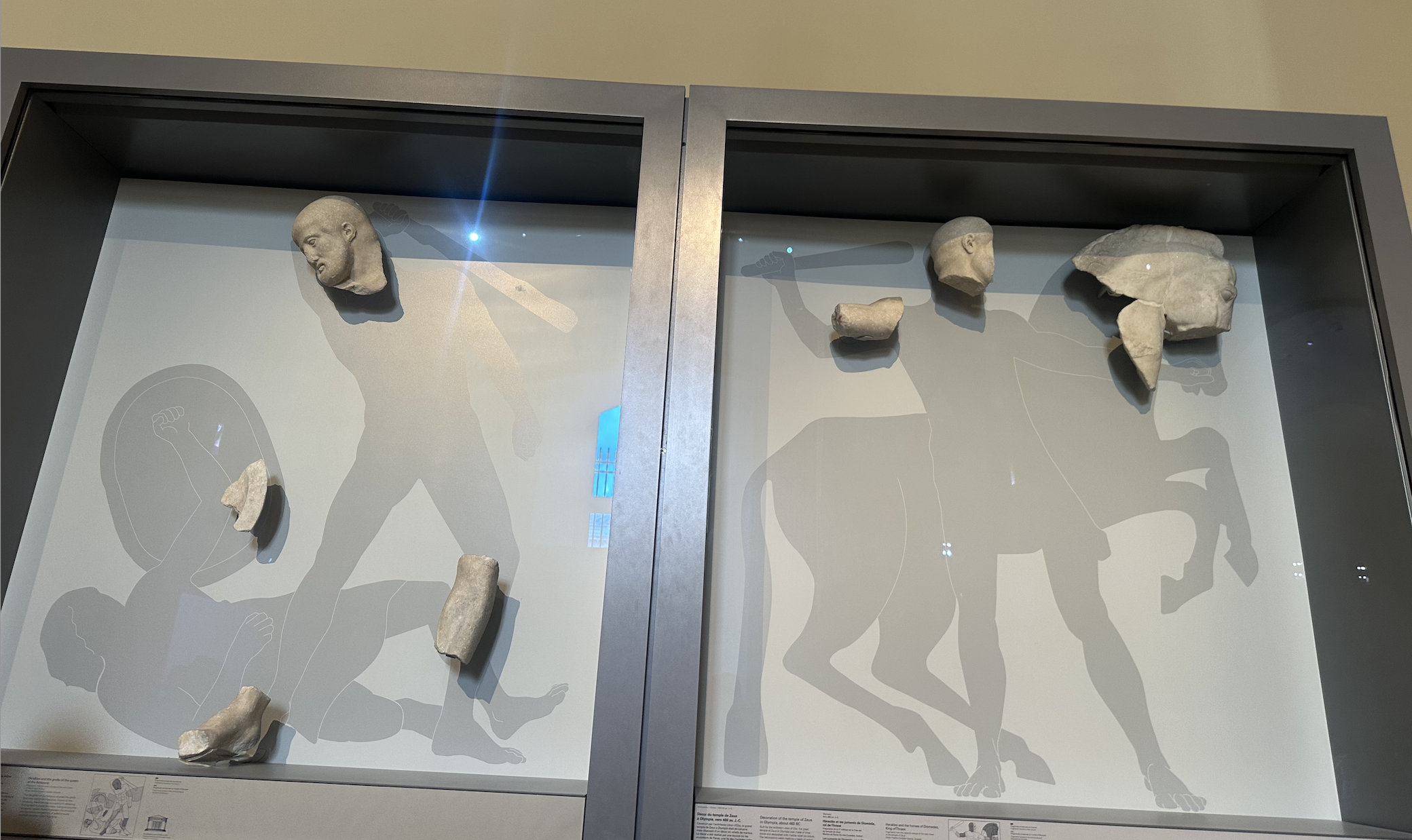

Later, I passed a sculpture that had remaining parts of the carved stone from two different sketches. The background was transparent, and I could see where the stones went. But the process of historians piecing it together amazed me. How difficult. It reminded me of Hugo's craftsmanship of Les Misérables. A hundred pages on a random bishop. An entire chapter on the Battle of Waterloo. At first, I kept asking, What does this have to do with a convict and a girl?

But like the sculpture, the parts eventually come together.

That bishop becomes the moral foundation of the book. The Battle of Waterloo leads us to meet Marius's dad and Thenardier. Each side's narrative, like each piece of stone, plays a role in shaping the whole. You don't see it all at once.

I made my way up to the top floor, where it's quieter and less crowded. I passed beautiful paintings: icebergs, a dog longing for food. I stop dead in my tracks at a painting by Pierre Narcisse Guerin. A portrait of a young girl, bare-chested, holding herself protectively, with short hair. Her eyes looked forward with a quiet, unwavering sadness. It was Fantine.

At first, the young girl appears calm and composed, almost classical. But the longer you look, the more you see it. There is endurance behind her. Pain she's learned to wear like skin. Fantine, too, was exposed and discarded by society. She sold her hair, teeth, and body to protect Cosette. The girl's gesture, shielding herself, echoes Fantine's loss of control and stolen innocence. And yet, she doesn't collapse. She remains human through the inhumane things she went through.

Looking back, the Louvre was not just about seeing famous works. As I searched for Les Misérables in frames and sculptures, I found the meaning. These characters weren't just figures in a novel, but a living reflection of human emotion and struggle in paintings, sculptures, and more.

As a student grounded in science, it's easy to get caught up in logic. But art like this, and stories like Hugo's, remind me why I'm here in the first place. Not just to sustain life, but to understand it. To feel it. You just have to look closely enough.