It was almost sunset as we bookpacked our way to the bridge, a light breeze shifting the water of the Seine. As we stood upon the overpass where Javert met his end, I couldn’t help but reflect on my understanding of said character. I was first introduced to Les Miserables when I was young, and I had been absolutely obsessed with it. But little Luna had been puzzled by the character of Javert, specifically by the choices he made. It had seemed a bit confusing, back then, that this rigid, intense, and unrelenting symbol would fold so suddenly. That he couldn’t accept his new worldview, could change himself upon being shown kindness, couldn’t work to therefore grow and change himself in the same way Valjean had. But as I looked over those railings on the bridge, I considered not just what Javert symbolized, but who he was.

Javert is a character who is most defined by his rigidity in all aspects of life - most of all in his world view. He is extremely hard-lined, obeying rules, policies, and laws to an absolute T—often going overboard in his devotion. He believes that the world is purely black and white, with absolute goodness being found in the law, and absolute bad being within criminals. But the world is not pure black and white, but is instead a kaleidoscope of grey. One of the greatest themes of this novel is that the law can be corrupt, discriminatory, and unjust, and can be wrong in how it enacts justice. Likewise, good people can break laws out of a need to survive, not out of evil intentions or a malicious nature. Javert can therefore be understood as a man defined by his blind righteousness and naive justice, a protagonist in his mind but an antagonist in the book.

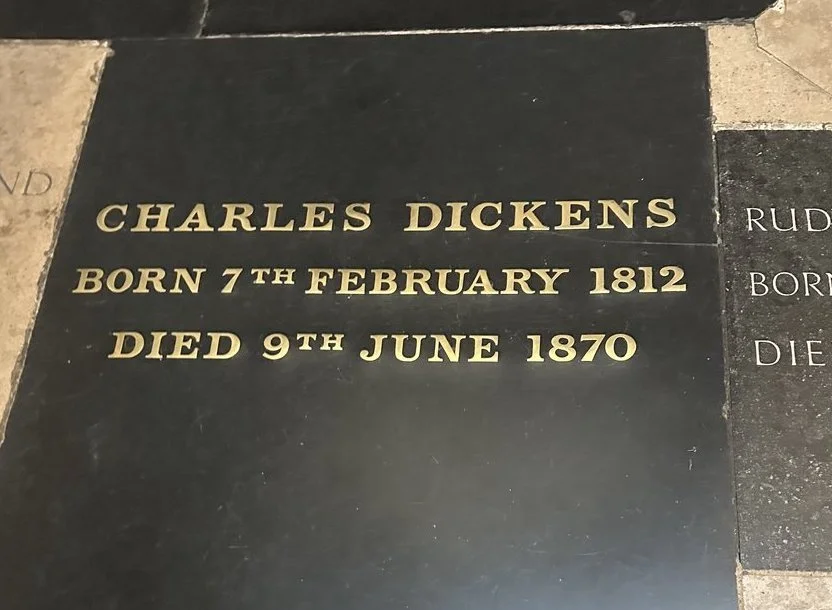

Javert’s intense allegiance to the law doesn’t just affect the way he views others, but how he treats himself. He himself recognizes the fact that he is extremely strict with himself, which presents in all aspects of his life. For starters, he always makes sure his police uniform is perfect to the highest degree. He holds himself to such high standards, to the point where his collar buckle being slightly below his ear and not behind his nape is an indication of “one of those emotional upheavals inside him that might be called an inner earthquakes,”(Dickens, 290).

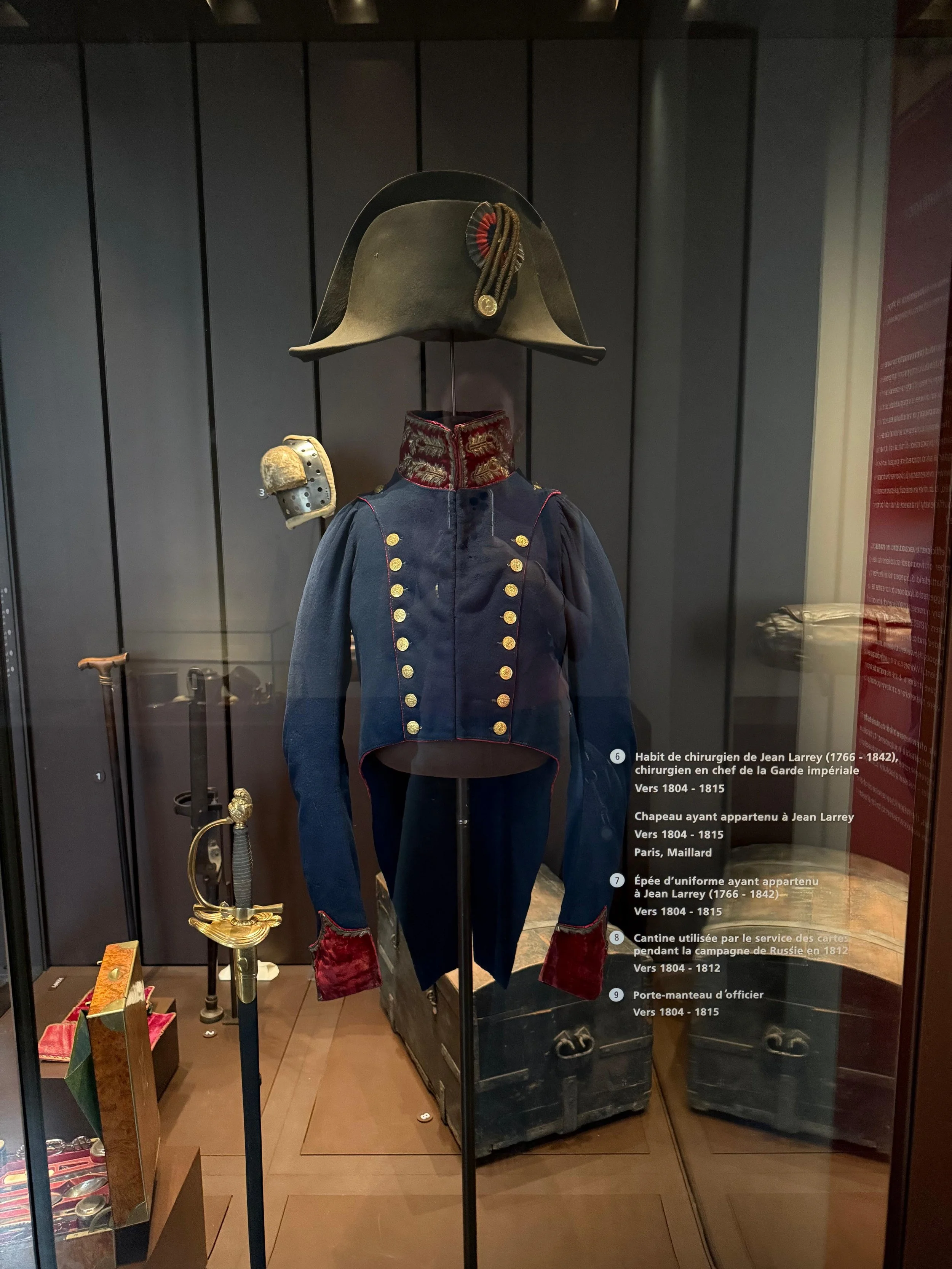

I don't think I truly understood just how extreme this level of uniform compliance would have been until we bookpacking the Musée de l'Armée. Although the specific police uniform Javert would have worn wasn’t there, there were enough from that time period for me to understand the sheer amount of buttons, straps, and buckles these uniforms had. For me, the fact that Javert’s collar buckle being slightly off indicating severe inner turmoil really hammers just how hard-lined he is.

Beyond his presentation, Javert demonstrates an urgent need to obey rule to an extreme degree, harshly punishing himself for any misstep. When he thought he’d mistakenly reported Madeline for Valjean, therefore committing insubordination, Javert demands that he be immediately fired. For a man defined by his need for justice, he is so quick to give up everything he defines himself by. There is no room for nuance, understanding, or sympathy for both himself and others, just pure black and white.

But why is Javert like this? While it would be easy to paint this policeman as a surface level villain who needs no explanation for his actions, reflections on his childhood reveals further depth and complexity in this character. A fundamental part in my own understanding of Javert comes from exploring his background, which despite being scarce is extremely informative. He was born in prison to a mother and father who were incarcerated, and likely spent his early years within the hulks. This is a completely unexpected origin for an officer of the law, and the point at which Javert changes from a prison inhabitant to a guard is unclear. Another crucial detail is that Javert is specified to be a Romani man, a group which has historically faced harsh discrimination, racism, and are treated as perpetual outsiders and intruders.

How would an environment that is described to turn the best of men into the worst affect a toddler? How would a child internalize the harsh and rigid structure of prison? Because of his childhood, I believe Javert is a product of his upbringing more than any inherent attributes. From a very young age, he was witness to how people were literally split into two groups, the prisoner and guard, the attacker and protector, the evil and good. As described in the novel, he was an outsider to this society, neither the prisoner nor guard, and thus “had a choice between these two classes only”. When choosing between the described “attacker” or “protector” of society, he chose the path of the latter. Another factor which would have contributed to this choice would be Javert’s own opinions on his background and identity. It is explicitly stated that his “inexpressible hatred” for his ethnicity was one of the reasons why he chose to become a police officer. In the same vein, it’s likely that he feels similar shame and self-hatred over the fact his parents are both inmates. Javert therefore uses his identity as a police officer to both distance himself from these ‘bad’ parts of his identity, while simultaneously joining the side of the perceived ‘good guys’.

From this, I can conclude that Javert could view criminality as a failure of character, and the breaking of laws as an act of pure evil. In Javert's mind, where the law is good and always correct, he rose out of his difficult childhood without breaking laws because he is a good person. Someone’s inability to do the same without breaking the law therefore means they are a fundamentally bad person. The law is never wrong, and criminals always are. This therefore works to inform his actions throughout the novel. Javert spares no sympathy for the struggles and suffering of Fantine, because in his mind, she is a fundamentally bad person.

However, his entire worldview got flipped upside down when Valjean both saved Javert and offered himself up to him. Suddenly, that which was fundamentally bad is good, and the law which commands Javert to arrest Valjean is wrong. This goes against everything that the inspector knows, and this revelation breaks him. Perhaps if this had been another person, they could have grown and continued forward with life. But the very nature of who Javert is makes this impossible. His beliefs have been ingrained into his since childhood, and is what he defines his life by. If that was wrong, what else is? He therefore recognizes that he is in the wrong and, in line with his past behavior in the Madeline incident, believes he must be punished. He therefore chooses to

““set about handing in his resignation to God””

So now - hearing the swells of the river, feeling the breeze on my face, seeing that greenish-blue water - I can’t help but think of Javert. Of the man so rigid and uniform, so extreme yet native. I think of the child who, born into a prison, was raised in the cruelty and abuse inherent in the justice system. Another character who is not inherently bad, but is simply a product of their environment. Bookpacking has opened my eyes to the fact that Javert was not just a one-note villain, but another of the “Miserables”.