“We passed whitewashed walls and great courtyard gates that revealed distant lamplit courtyard paradises like our own, only each seemed to hold such promise, such sensual mystery. Above, figures sat on the balconies, their hushed voices and the flapping of their fans barely audible above the soft river breeze. Occasionally a figure dressed for evening appeared at the railings, the glitter of jewels at her throat, her perfume adding a lush evanescent spice to the flowers in the air…”

We're in New Orleans - we arrived last Thursday.

I went for a stroll as soon as we arrived, and the streets were full of music from an open-air festival in Lafayette Square just next to our hotel, and people were spilling off the sidewalks with little care for traffic, and it was all so relaxed and happy I couldn't help smiling. We headed out for a team dinner in the Little Gem Saloon on Rampart Street, where a grizzled musician played slide guitar and sipped a bourbon, and we ate a taster menu of Creole and Cajun food (Andouille sausage, fried catfish, red beans and rice, shrimp and grits), and every plate was ridiculously delicious. And all this within three hours of our arrival. Honestly, I love this city.

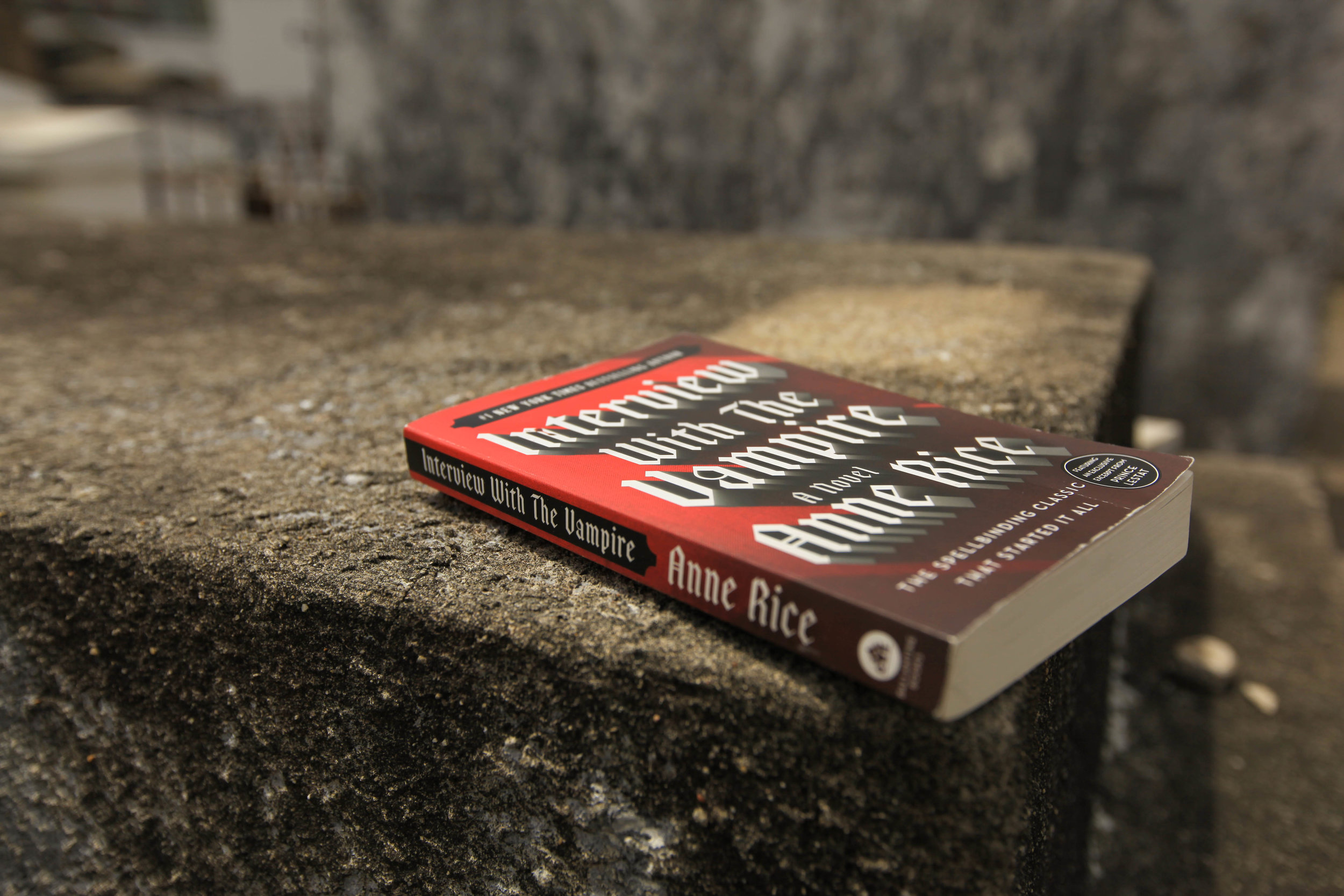

We’re reading Anne Rice's 'Interview With a Vampire', the first of three books I've chosen for our time in New Orleans. It's a glorious slice of New Orleans gothic, the first in Rice’s series of novels about the vampire Lestat. It’s an easy read, full of sumptuous and arresting images, and there’s no better book to introduce the French Quarter, the tourist heart of the city.

The novel begins in 1795, right at the end of the French / Spanish colonial period. At that point the French Quarter was all there was - a small grid of streets bordered by ramparts and the Mississippi river. The streets have French names - Bourbon, Chartres, Dumaine - and the architecture is Creole / Spanish. This is the vampire Lestat’s New Orleans.

It's such an evocative time in New Orleans history. Louis, the novel's narrator, is a rich young Creole. His indigo Plantation, Pointe du Lac, is just downriver, and like other planter families he and his mother and sisters come to New Orleans by carriage to visit the opera and the theatre. Anne Rice is brilliant at capturing the intoxicating flavour of New Orleans in those years, the lush decadence, the polyglot mix of ethnicities, the gas-lit streets, the hint of danger.

Forgive me, here, if I quote a lengthy section. This is Louis, describing the city in the late colonial and early American period:

There was no city in America like New Orleans. It was filled not only with the French and Spanish of all classes who had formed in part its peculiar aristocracy, but later with immigrants of all kinds, the Irish and the German in particular. Then there were not only the black slaves, yet unhomogenized and fantastical in their different tribal garb and manners, but the great growing class of the free people of color, those marvellous people of our mixed blood and that of the islands, who produced a magnificent and unique caste of craftsmen, artists, poets, and renowned feminine beauty. And then there were the Indians, who covered the levee on summer days selling herbs and crafted wares. And drifting through all, through this medley of languages and colors, were the people of the port, the sailors of the ships, who came in great waves to spend their money in the cabarets, to buy for the night the beautiful women both dark and light, to dine on the best of Spanish and French cooking and drink the imported wines of the world. Then add to these, within years after my transformation, the Americans, who built the city up river from the old French Quarter with magnificent Grecian houses which gleamed in the moonlight like temples. And, of course, the planters, always the planters, coming to town with their families in shining landaus to buy evening gowns and silver and gems, to crowd the narrow streets on the way to the old French Opera House and the Théâtre d’Orléans and the St. Louis Cathedral, from whose open doors came the chants of High Mass over the crowds of the Place d’Armes on Sundays, over the noise and bickering of the French Market, over the silent, ghostly drift of the ships along the raised waters of the Mississippi, which flowed against the levee above the ground of New Orleans itself, so that the ships appeared to float against the sky.

This was New Orleans, a magical and magnificent place to live. In which a vampire, richly dressed and gracefully walking through the pools of light of one gas lamp after another might attract no more notice in the evening than hundreds of other exotic creatures—if he attracted any at all, if anyone stopped to whisper behind a fan, ‘That man … how pale, how he gleams … how he moves. It’s not natural!’ A city in which a vampire might be gone before the words had even passed the lips, seeking out the alleys in which he could see like a cat, the darkened bars in which sailors slept with their heads on the tables, great high-ceilinged hotel rooms where a lone figure might sit, her feet upon an embroidered cushion, her legs covered with a lace counterpane, her head bent under the tarnished light of a single candle, never seeing the great shadow move across the plaster flowers of the ceiling, never seeing the long white fingers reached to press the fragile flame...

Wonderful - the heady brew of New Orleans.

These were the paragraphs I read out in my first session on campus, introducing the students to the idea of bookpacking and enticing them to join me on this journey. And here we were now, walking these very streets, seeking out hidden corners and shady courtyards, and seeing them through Louis’ eyes.

Today, the French Quarter is a tourist mecca. Horse drawn carriages carry tourists through the streets, and musicians busk for the passers by. It’s truly beautiful, one of those rare places in the US (like Williamsburg and Charleston) were the colonial world has survived intact. Creole townhouses line the streets, vines creep on wood and brick and railing, and the sidewalks (or banquettes, I should say) are uneven. Distressed gentility, with the suggestion of opulence within.

In the novel, Louis is himself transformed into a vampire, and he lives with Lestat on Royal Street. Their house is full of luxuries from France and Spain: ‘crystal chandeliers and Oriental carpets, silk screens with painted birds of paradise, canaries singing in great domed, golden cages, and delicate marble Grecian gods and beautifully painted Chinese vases’. Every window we passed offered (in Rice’s words) ‘such promise, such sensual mystery’. Every courtyard we passed, I hoped to see the fountain that marks Lestat’s house, ‘with a stone nymph pouring water eternal from a widemouthed shell’ - it’s there on Royal Street, somewhere, surely.

On the walls of the old Ursuline Convent we studied a map of Lestat’s New Orleans - the city in the 1790s. Beyond the rampart walls, in charcoal, was written one word: 'Swamps'. Back then, this part of the lower Mississippi was a dank landscape of cypress swamps, and the atmosphere of the swamps pervade the novel. There is a dark lushness to Anne Rice’s prose, a humidity to the writing. At one stage in the novel Louis attempts to kill Lestat, and he dumps him - where else? - in the swamps. He imagines him,

‘... sunk deep among the roots of cypress and oak, that hideous withered form folded in the white sheet. I wondered if the creatures of the dark shunned him, knowing instinctively the parched, crackling thing there was virulent, or whether they swarmed about him in the reeking water, picking his ancient dried flesh from the bones.’

I wanted to give my students a sense of this swampland, the fetid landscape in which the early French colonists chose to build their city. So, en route from Grand Isle, we stopped at the Barataria Preserve, a wetland half an hour south of New Orleans. The swamps didn’t quite match my expectations - the cypress trees were less than a century old, and I had something more primordial in mind. But of course all those massive cypress trees were cut down in the colonial period to provide wood to build the city. Cypress, as a local guide explained, is New Orleans’ “wonder wood” - it’s strong, it’s waterproof, it doesn’t rot, and termites hate it. The houses of the French Quarter are all built in cypress, with soft Mississippi brick providing ballast between the structural cypress posts - a style of building they called ‘briquette-entre-poteaux’, bricks between posts.

We had a happy hour walking the boardwalk through the wetlands, watching out for alligator (none to be seen, sadly). We photographed lizard and dragonflies, and listened to the bleating of the frogs. The cypress trees may have lacked size, but they were still atmospheric and spectral, rising from the dark water with Spanish moss trailing from their limbs.

Since that first day in the French Quarter we’ve had a chance to explore beyond. Vampires, of course, are immortal - and that’s a boon for bookpackers. Rice’s characters survive the decades, and using the novel as a guide, we’ve traced the development of New Orleans beyond the rampart walls as the swamps were drained and plantation land sold for housing.

Yesterday we went to the Garden District a rich and beautiful suburb founded uptown by the Americans that arrived in New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This was where Anne Rice lived when she became a best-selling author. She restored a decayed mansion and lived here with her family. The house is known now as the Anne Rice House, although the mansion was originally called ‘Rosegate’ after the rose patterns on the railings. Like all the mansions in the neighbourhood, it’s large and lovely, with a vast balcony and set in a comfortable garden - but even this generous property is dwarfed by some of the mansions nearby, 20,000 square-foot monsters in the antebellum style, a testament to New Orleans in the boom days of cotton. (I’ll write more about this in another post).

Just down the road from the Anne Rice house is the Lafayette Cemetery. The cemeteries of New Orleans are rightly famous, and this is the most atmospheric - a city of the dead. The tombs are both Catholic and Protestant, the French names outnumbered by those of Anglo-American, German, Italian and Irish families. But all ape the Catholic style of raised tombs - no ‘six feet under’ here. Protestants who tried to bury their loved ones in the ground found that, in times of flood, the coffins bobbed up and knocked ominously on the burial slabs. So raised tombs became the norm, and here in the Lafayette Cemetery you walk through avenues lined with grey mausoleums, the white stucco fading and grass and weeds pushing their way through every crack.

In the novel, Louis and Lestat adopt a five year old girl, Claudia, whom they find bereft beside the corpse of her mother, a victim of yellow fever. Transformed into a vampire, Claudia grows up, trapped in a five-year-old body - and the Lafayette Cemetery is where she comes to hunt for victims.

‘She had asked to enter the cemetery of the suburb city of Lafayette and there roam the high marble tombs in search of those desperate men who, having no place else to sleep, spend what little they have on a bottle of wine, and crawl into a rotting vault.’

As I said, the novel is full of arresting images. It may not be great literature, but reading 'Interview With The Vampire' in New Orleans is a great way to bring the city alive, in all its dank, decadent, superstitious, transgressive and nocturnal glory.

Bring the novel when you visit - and sleep tight if you can…