“The roar would swell and rise and fall and swell again, with the Boss standing with his right arm raised straight to Heaven and his red eyes bulging.”

We’re in Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s State Capitol, and ahead of me stands the Capitol Building, an impressive 450-foot tower built in the early Depression years by Huey Long, Louisiana’s populist governor and quasi-dictator. Huey himself stands in front of me on his funereal monument, his hand extended in gracious largesse, although a clenched fist would have been more appropriate.

We're here reading Robert Penn Warren’s ‘All the King’s Men’, written in the 1940s and based on Huey Long’s life - and in the current political climate I can’t think of a novel that’s more pertinent or important.

‘All The King’s Men’ describes the political rise of a demagogue, Willie Stark, a hick lawyer who talks a hick language and rises to power by telling the hicks ‘of the bayous and the burnt-over lands’ that he is their salvation, that he will talk for them and fight for them, clearing out the swamp of entrenched interests with a political methodology that is bruising and direct. He declares to the roar of the crowd that:

“If any man tries to stop me in the fulfilling of that right, I’ll break him. I’ll break him like that! I'll smite him. Hip and thigh, shinbone and neckbone, kidney punch, rabbit punch, uppercut, and solar plexus. And I don't care what I hit him with. Or how!"

There’s nothing hyperbolic about Robert Penn Warren’s portrayal of Willie Stark. Huey Long really did talk like this. He surrounded himself with henchmen packing revolvers, he blackmailed senators, he stuffed all levels of Louisiana’s administration with his supporters and created a pyramid of graft. But also, he got things done. He built highways and hospitals and schools, and dragged Louisiana, the poorest and most illiterate state in the US, into the 20th century. In 1933 he launched a nationally popular program, Share Our Wealth, promising to strip the assets of the wealthiest Americans. By 1934 he stood ready for a bid for the White House.

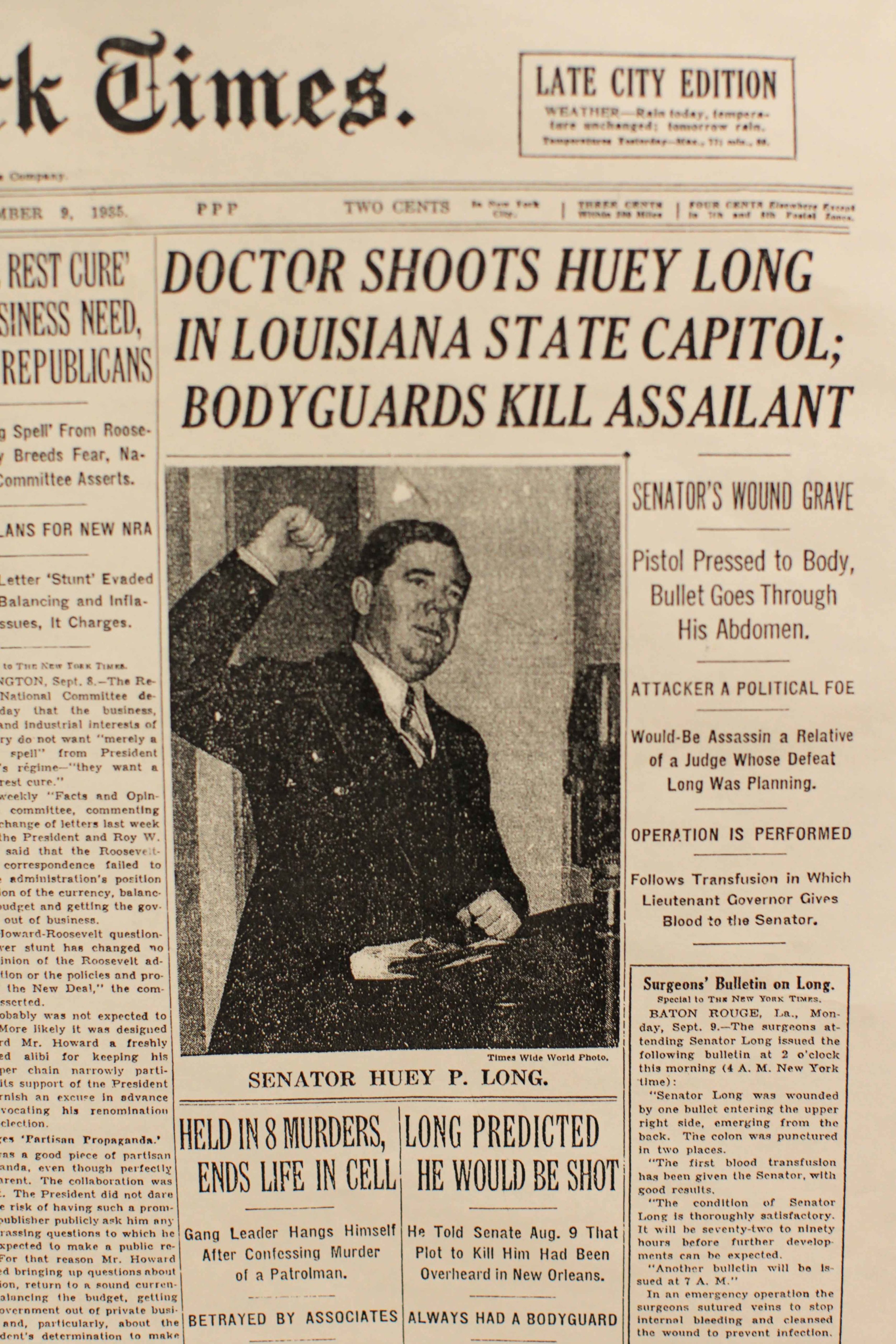

He could have succeeded, too, given the turbulence of the times. But in September 1935 he was gunned down by a disaffected citizen in the lobby of the Capitol Building which stands now as his testament.

As you can imagine, we’ve had a fascinating time, my students and I, discussing the political career of this colourful character, cyphered in fiction through the figure of Willie Stark*. He reads as a contemporary composite, an economic populist like Bernie Sanders with the self-confidence, swagger and realpolitik of Donald Trump. We’ve talked about American politics, and how stable it is, or not, and how 2016 changed everything and made a political cautionary tale from the 1930s seem so contemporary and real. And we’ve talked about ends and means, and ‘dirt’. In the words of Willie Stark:

“Dirt's a funny thing. … Come to think of it, there ain't a thing but dirt on this green God's globe except what's under water, and that's dirt too. It's dirt makes the grass grow. A diamond ain't a thing in the world but a piece of dirt that got awful hot. And God-a-Mighty picked up a handful of dirt and blew on it and made you and me and George Washington and mankind blessed in faculty and apprehension. It all depends on what you do with the dirt. That right?”

Driving to Baton Rouge we took the Airline Highway, one of the roads Huey Long built in his time in office. (Before his tenure, Louisiana had only 300 miles of paved road in the entire state - imagine that!). It’s an extraordinary road, with lengthy sections constructed on raised concrete pillars suspending the highway over the swamplands on either side, vast acres of cypress rising from the dark brown water. We were reminded of Ignatius in ‘A Confederacy of Dunces’, taking an ill-fated trip to Baton Rouge in a Greyhound Scenicruiser. He describes how outside New Orleans, ‘the heart of darkness, the true wasteland begins’.

‘Speeding along in that bus was like hurtling into the abyss. By the time we had left the swamps and reached those rolling hills near Baton Rouge, I was getting afraid that some rural rednecks might toss a bomb into the bus. They love to attack vehicles, which are a symbol of progress, I guess’.

We’re not planning on this trip to venture far into the northern half of the state, but compared with the Cajun and Creole South - and New Orleans, specifically - Northern Louisiana is another world, a part of the Protestant Deep South. It was colonized in the early 19th century by poor white farmers - the “Kaintucks”, as they were known - who moved here down the rivers of the trans-Appalachia. The state capitol was switched from New Orleans to Baton Rouge in 1846, in part to create some geographic parity, but more importantly because the Protestant North was suspicious and resentful of (as they saw it) that 'immoral Sodom', New Orleans. In the years after the Civil War, the forests were stripped by wealthy Yankees and the land turned to arable and coal, and the decades passed, and the poor white farmers atrophied, and waited for a saviour.

‘All The King’s Men’ captures all this brilliantly. A lengthy sequence early in the novel brings Willie Stark and his entourage home to his father’s rural homestead in the northern part of the state (Huey Long was born in Winnfield, LA). Standing by the pig pen, Willie recollects the amount of swill he poured as a child – “and By God, I’m still doing it. Pouring swill." The novel’s narrator Jack Burden imagines Willie as a child, burning with ambition, sitting on in his tongue-and-groove bedroom listening to the winds that have come a thousand miles from the Dakotas, battering the house. ‘He wouldn't have any name for what was big inside him. Maybe there isn't any name’.

For me, as much as anything, the process of Bookpacking is about encouraging a process of empathy, walking (as Atticus Finch puts it) in the other person’s shoes. It today’s divided America it’s necessary more than ever, and I felt it during the election season last year, watching the crowds on television at Trump’s rallies, listening to ‘the roar’. What do they think, these disaffected folks of the rust belt, or here in Louisiana, in ‘the bayous and the burnt-over lands’? What do the cities look like to them - New York and Washington and Los Angeles, and New Orleans, that place of cosmopolitan otherness?

Last year they found their saviour, and - unlike Huey Long - he made it to the White House, and we live in the echo of that roar.

'He turned and walked slowly back into the tall doorway of the Capitol, into the darkness there, and disappeared. The roar was swelling and heaving in the air now, louder than ever. I stared into the darkness of the great doorway of the Capitol, where he had gone, while the roar kept on.'

* nb we read the restored edition, in which the character is called "Willie Talos" as per Robert Penn Warren’s original manuscript. I’ve used “Willie Stark” in this post because that’s the name by which he’s most commonly known.