“‘His great diocese was still an unimaginable mystery to him. He was eager to be abroad in it, to know his people; to go westward among the old isolated Indian missions; Isleta, whitened with gypsum; Laguna, of wide pastures; and finally, cloud-set Ácoma’.”

We’re standing high above the New Mexico desert, at the top of a Mesa - one of those distinctive flat-topped hills that add such drama to the extraordinary landscape of America’s southwestern desert region.

This particular Mesa, 350 feet high, has been home to the Ácoma people for a thousand years. Nicknamed ‘Sky City’, It’s the oldest place of continuous human habitation in the USA. We’re being shown round by Brandon, an Ácoma guide, who talks with charm and insight about his people, for whom the pueblo on Ácoma Mesa was a place of peace and sanctuary against the incursions of the nomadic and warlike Navajo.

We’ve here on a ‘bookpackers’ pilgrimage.

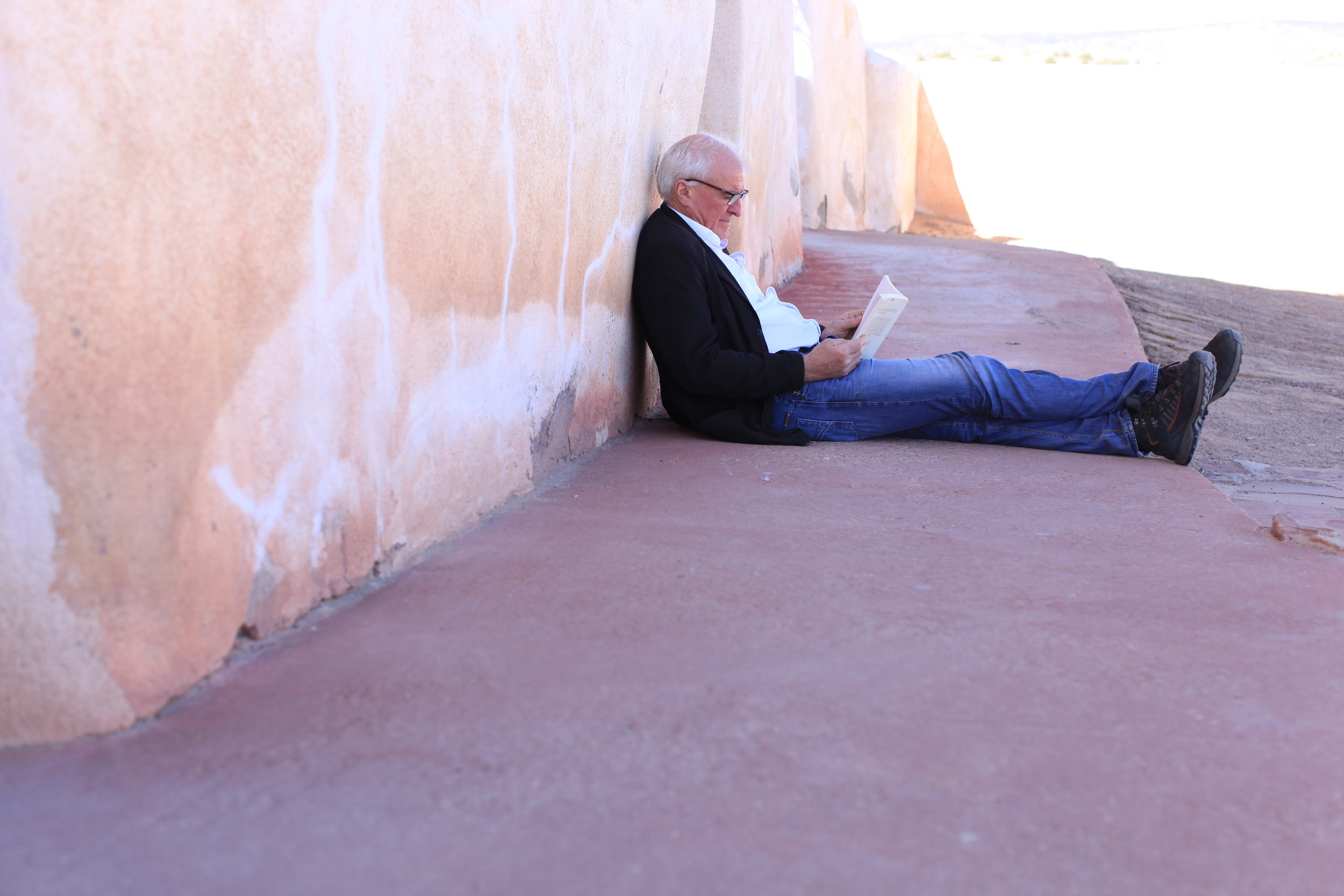

We’re reading Willa Cather’s wonderful 1927 novel ‘Death Comes for the Archbishop’. It’s the story of a Catholic priest in New Mexico in the years that followed US annexation. Father Latour, Cather’s hero, is a cerebral, compassionate man, charged with the seemingly impossible task of restoring Catholic piety to this remote frontier. At one pivotal point in the novel, Latour comes here to Ácoma to celebrate mass in St Stephen’s, the fortress-like church that stands on the southern cliff-edge of the Mesa - and we’re walking in the fictional Latour’s footsteps.

It’s wonderful to be ‘bookpacking’ again. I love the experience of reading a novel on the road. And ‘Death Comes for the Archbishop’ is the perfect example of a ‘bookpackers’ novel, full of vivid natural descriptions and rich perspectives into the history of the region. It tackles head-on the interplay of cultures that define New Mexico. Latour mixes with the old Hispanic ranchero families, Native Pueblo tribes, Western frontiersmen, and Johnny-come-lately Anglo settlers. Cather doesn’t skimp on the atrocities and tragedies that have shamed these bloodlands - Kit Carson’s massacre of the Navajo at the Canyon de Chelly is described at the end of the novel, for instance - but at least through Latour’s empathetic eyes, we come to see how mutual understanding can forge something new out of centuries of struggle.

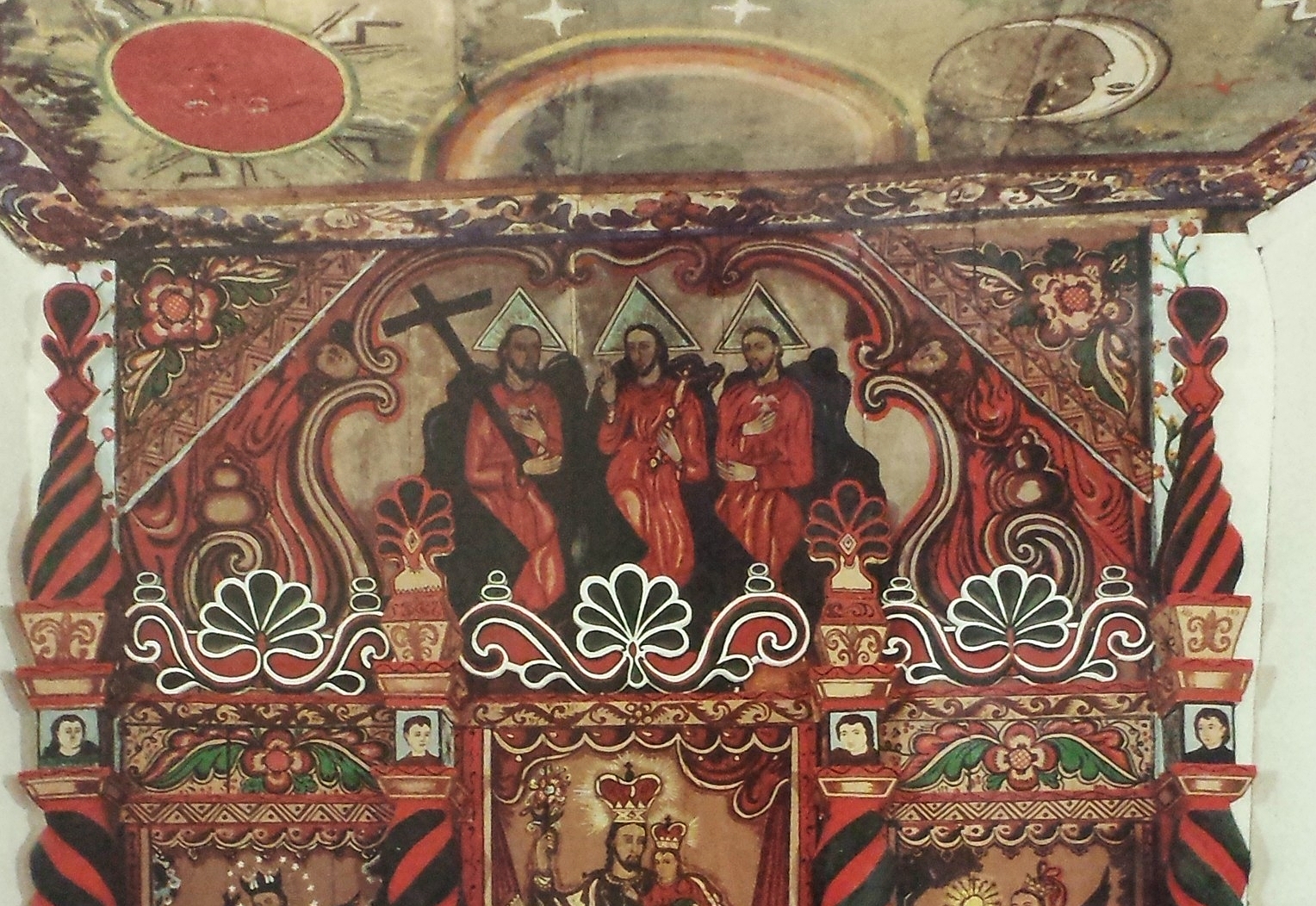

Here at Ácoma, this uneasy rapprochement is tested. The Mesa sanctuary was taken by Spanish conquistadors in the late 16th century, and they exacted a terrible revenge on the resistant Ácoma, cutting off the right foot of young men of the tribe, and enslaving others. The massive Mission church of St Stephen’s stands as a testament to conquistador arrogance, and as Latour celebrates mass here he is received in sullen silence. ‘When he blessed them and sent them away, it was with a sense of inadequacy and spiritual defeat.’

As he examines the fortress-like church, he wonders, ‘what need had there ever been for this great church at Ácoma?’. He asks about the massive beams holding up the roof and hears how the Ácoma people were forced to carry these beams through the desert from the sacred mountain (now Mount Taylor) thirty miles to the north. He concludes with some understatement, the Spanish priests that forced this endeavor were ‘not altogether innocent of worldly ambition’.

Brandon, our guide, was keen to stress how the Ácoma hold no enmity. “There are good and bad in all people, and in all peoples”, he said. He talked about the Franciscans, particularly, with respect, describing the good they did amongst Hispanic peons and Pueblo natives alike. And today, many Native Americans in the desert Southwest are practicing Catholics, balancing their Christianity with native beliefs and traditions. Brandon was protective of the latter; he said it was frowned on for tour guides to discuss Native spirituality with tour parties. But he showed us a 'kiva', a chamber for ritual observances, marked out by a white ladder propped against the exterior held together with a cross strut carved to suggest clouds.

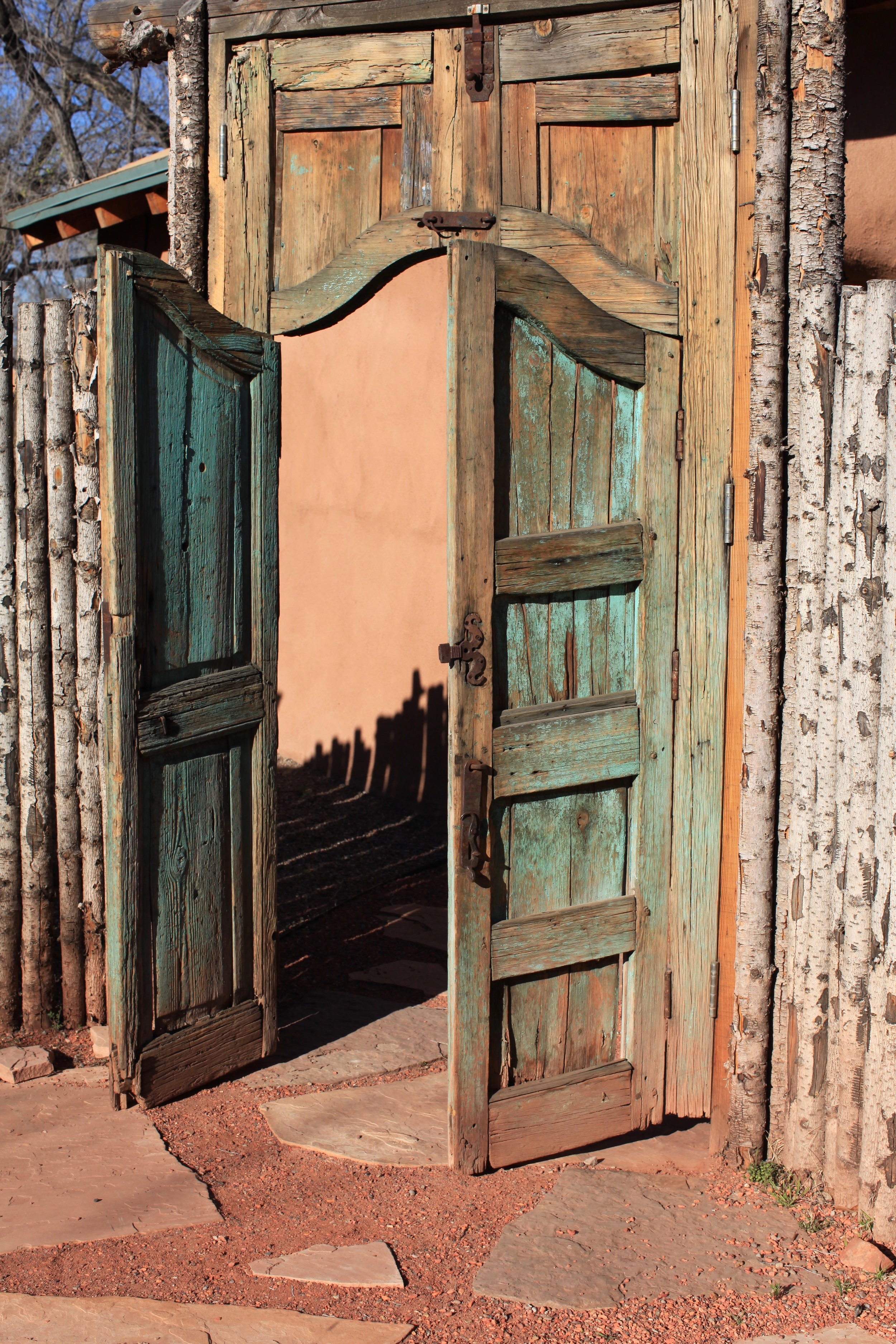

Visiting Ácoma has been on my bucket list for years. It wasn’t quite as I expected. It carries its antiquity lightly; pickups and gas canisters stand alongside traditional Mexican ovens, and houses are being repaired with contemporary breeze block rather than sticking rigidly to heritage guidelines. But that, I suppose, is the joy of this place - it’s a living community. Rather than being dispossessed (as happened to so many tribes, pushed west, shepherded onto reservations) the Ácoma are still where they’ve always been. The rock remains their sanctuary, and life goes on.

In the novel, Bishop Latour’s journey to the pueblos takes place in 1851, a year after his arrival in the region. New Mexico at that point was a new territory of the US, annexed after the Mexican-American war. At this point in history this slice of the present day USA had been under Hispanic control for a quarter of a millennium - first as part of New Spain, and then (after the 1821 Mexican Revolution) as part of Mexico. The region is peppered with Mission Churches, founded by the Jesuits and Franciscans, buildings founded here in the interior when the English, French and Dutch were merely scrabbling for a toehold on America’s eastern seaboard.

At the start of Latour’s episcopacy, New Mexico is described as place where Catholicism is barely holding on, a beleaguered northern outpost of Mexico were ‘there are no wagon road, no canals, no navigable rivers. Trade is carried on by means of pack-mules, over treacherous trails. … The old mission churches are in ruins. The few priests are without guidance or discipline. They are lax in religious observance, and some of them live in open concubinage’. It is ‘a land of old men trying to remember their catechism to teach their grandchildren’. But as Latour discovers, ‘the Faith planted by the Spanish friars and watered with their blood was not dead; it awaited only the toil of the husbandman’.

The metaphor of the husbandman pervades the book. Latour is a gardener; he plants his episcopal garden with cherries and apricots. And in the dry desert soil, something precious and beautiful takes root.

The highlight of my day was a conversation with an elderly Laguna woman, Sister Consolata, Native American by birth, Catholic by faith, a sister of the Blessed Order of the Sacrament. We talked in the shade of St. Joseph’s Mission Church in Laguna Pueblo, twenty miles north of Ácoma. Her shoulder and wrist were in a sling, and she told me how, next week, she was going to Chimayo, a place of pilgrimage north of Santa Fe, where a crucifix appeared in the desert to Don Bernado Abeyta, one of a brotherhood of ‘penitents’ living in the region in the early 18th century. In the church on the site there is a room with a hole in the ground, marking where the crucifix appeared. Dirt from the hole cures ailments. And as I listened, I thought of Willa Cather, and of how she would have loved this conversation. And I thought of Bishop Latour the husbandman, planting faith in New Mexico’s blood red soil.

This is part of a two part feature, continued here.