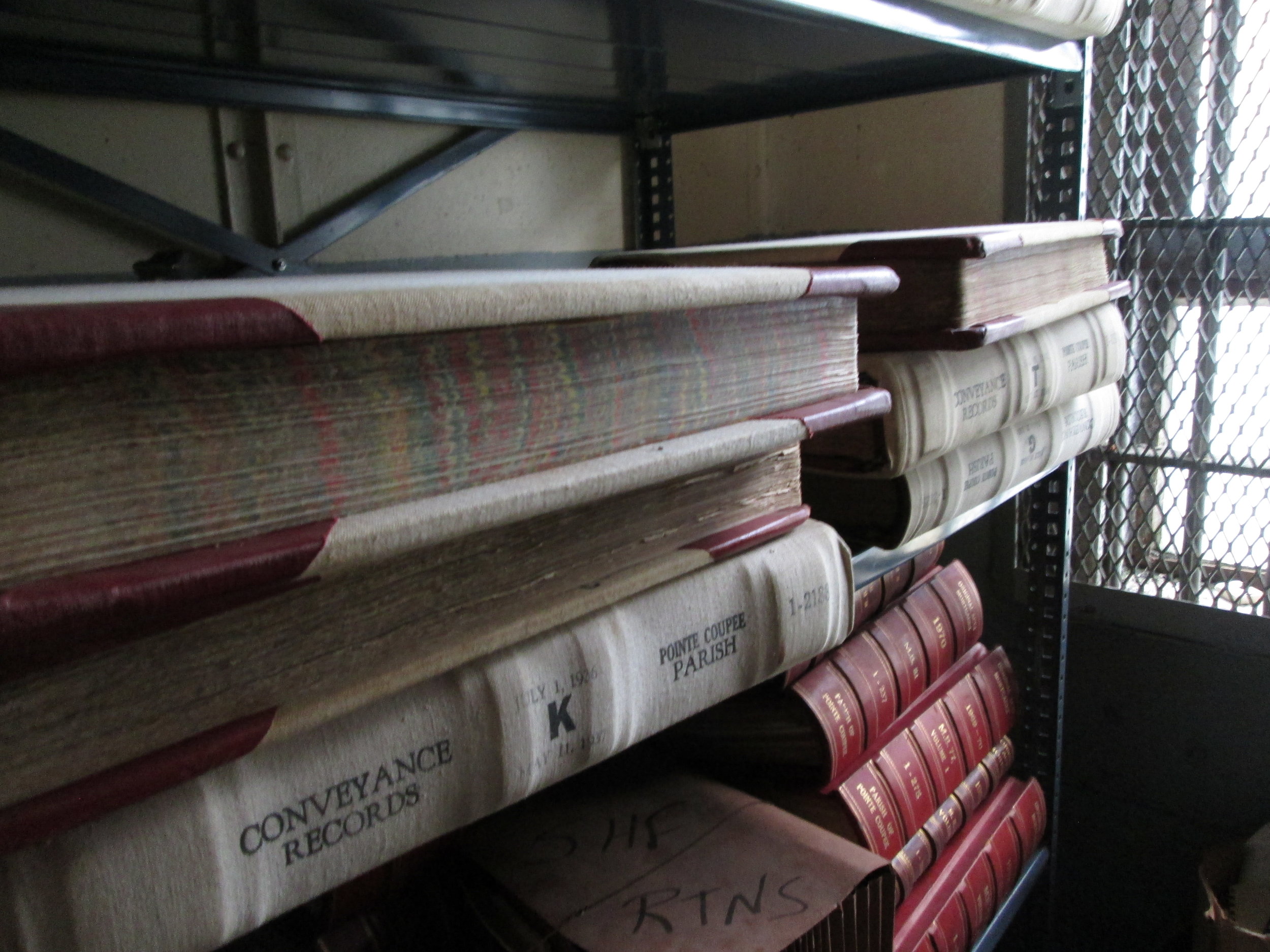

There's something special about reading literature in the place where it is set. I look around me and see the "balconies dripping iron lace" in New Orleans' French Quarter as described in The Moviegoer; Pirate's Alley and the cemeteries call to mind the fictional feet that wandered through these places in A Confederacy of Dunces and Interview with the Vampire. I have a deep appreciation for literature and its ability to transport me into another time, place, or culture that may vastly differ from my own. Reading and writing provide a link between worlds that would otherwise be separated. When I pick up a book, the power of the written word gives me a new lens with which to look at my surroundings; with "bookpacking", this power is amplified by my actual surroundings, and suddenly the history of the city feels alive and present.

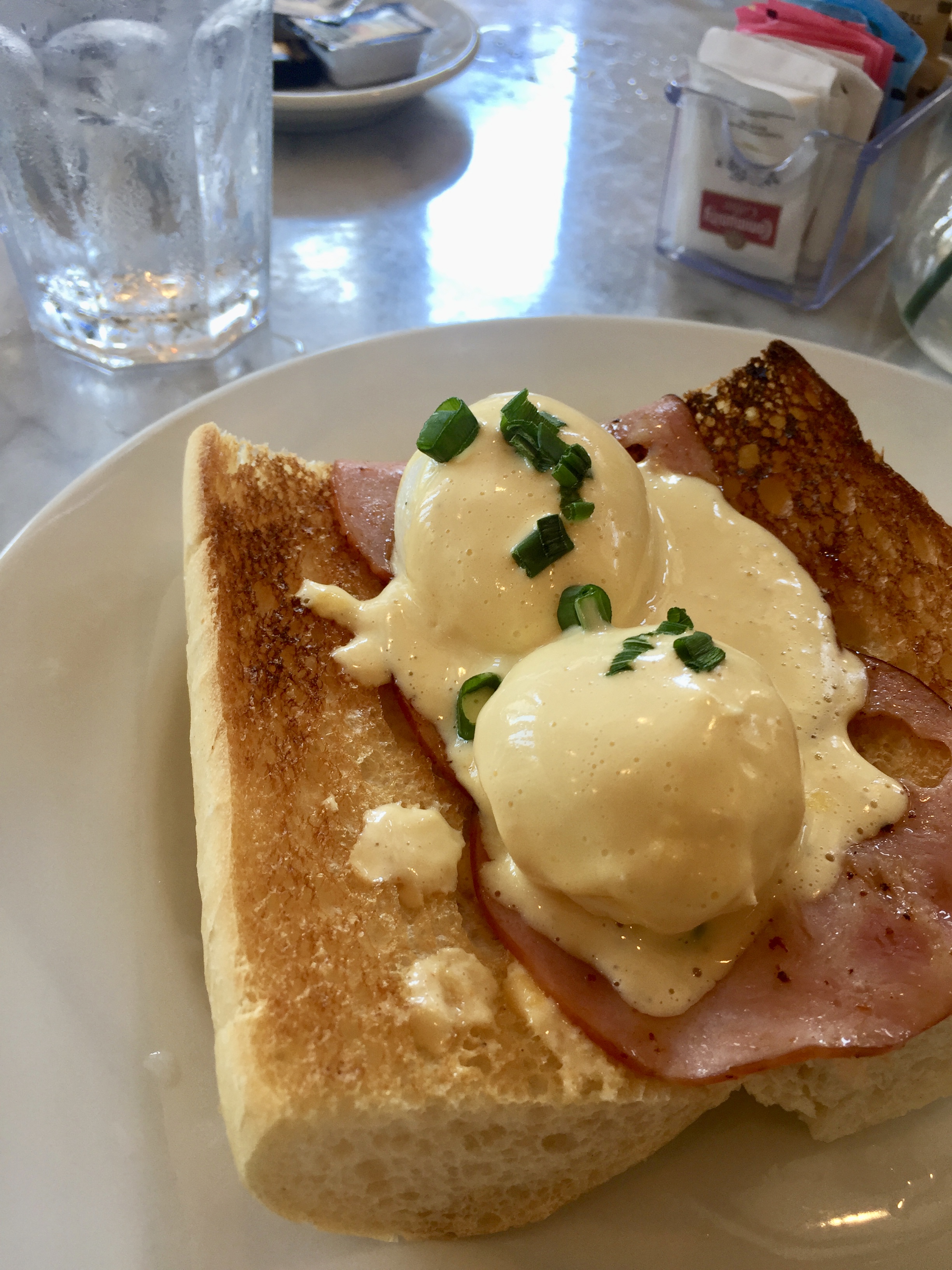

We've explored the beauty of jazz at Preservation Hall, danced in a Second Line parade, learned about Voodoo and the historical significance of the cemeteries, even visited the 9th ward and its reconstruction after Katrina. Meeting people who live here and listening to their stories has informed our experience as much as our novels have - and don't even get me started on how delicious the food is. New Orleans is a city filled with life and the promise to be who you want to be, regardless of where you came from or where you're going.

In this age of technological innovation and the struggling middle class, it's difficult to take time off to really cherish and explore a new place, which this trip has provided for us. The spirit of New Orleans is dedicated to fun, but it is also a city where families lounge on their porches in the evening hours and say hello to passerby. We took the time as a group to laugh together at cafés during sudden rainstorm, enjoying delectable beignets and absorbing the environment. The people of New Orleans have their resilient side, too; learning about the impact of Hurricane Katrina on this fun-loving community broke my heart, but the vibrancy of its return to its former state of celebration in the past twelve years proves to me that this unique culture cannot be tempered.

I've had a wonderful time exploring the artistic side of New Orleans on our travels. I visited the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and viewed paintings of artists from around the South that, to them, represent their distinct regional cultures. The art of James Michalopoulos, in particular, focused on New Orleans and captured the bright spirit of the city through his colorful paintings of houses, cars, and people, listening to the playful street music as part of his artistic process. Attending a jam session with the band The Tumbling Wheels at the museum later that night showed me the intertwining of artistic endeavors in this city, having a significant impact on how the culture thrives.

“Leaving New Orleans also frightened me considerably. Outside of the city limits the heart of darkness, the true wasteland begins.”

Artists, I've come to find, include the authors of literature themselves. The beauty of writers is they can capture the culture of a certain time and place with words in an effort to convey its uniqueness to those who may not have the chance to see it for themselves. The importance of writing true to a specific environment - accurately depicting the struggles and triumphs of characters as they interact with the culture they’re subjected to - reflects the diversity of human nature and the possibilities that may come about with travel and critical reading. Walking the same streets as Tennessee Wiliams and Ernest Hemingway and feeling inspired to write as they had was surreal.

My view of New Orleans has gone from bird's eye to first-hand. Unlike any travels I've done before, I feel now that I really know the city in a deeper way than if I had spent a whirlwind week vacation here. The amount of time being here (a month) coupled with bookpacking and learning about the city's history has made this experience incredibly immersive and so much more worthwhile. I'm disappointed to be leaving this city, but now I know that I will be back, as so many other artists of day's past have been inspired by this city's heart and returned to it.