With our initial journey of New Orleans having come to a close, our bookpackers group made our way to Baton Rouge to have one of the most incredible experiences of a lifetime. After a long drive full of great tunes and greater naps, we pulled up to the perfectly placed Hotel Indigo, which was just feet from the water but also close to cafes and shops. The lovely view from our room would not stay a view for long though, as we quickly decided to venture out.

Our first couple days in Baton Rouge were spent touring the capitol building, the courthouse, and, perhaps most jarringly, the thankfully no longer used prison cells of New Roads. While the cells were extremely run down, with paint flakes falling from the ceiling, it was easy to envision Jefferson, the falsely accused man of Ernest J. Gaines’ A Lesson Before Dying, sitting quietly on one of the bunks. The conditions of this prison were unimaginable, as it resided on the upper floor of the courthouse and had no air conditioning. As we all know, Louisiana is rather unforgiving when it comes to its astonishing heat, making even a quick tour of the facility unbearable. Seeing these cells and hearing about the conditions prisoners were subjected to made Jefferson even more of a sympathetic character who was put in a nightmare of a situation.

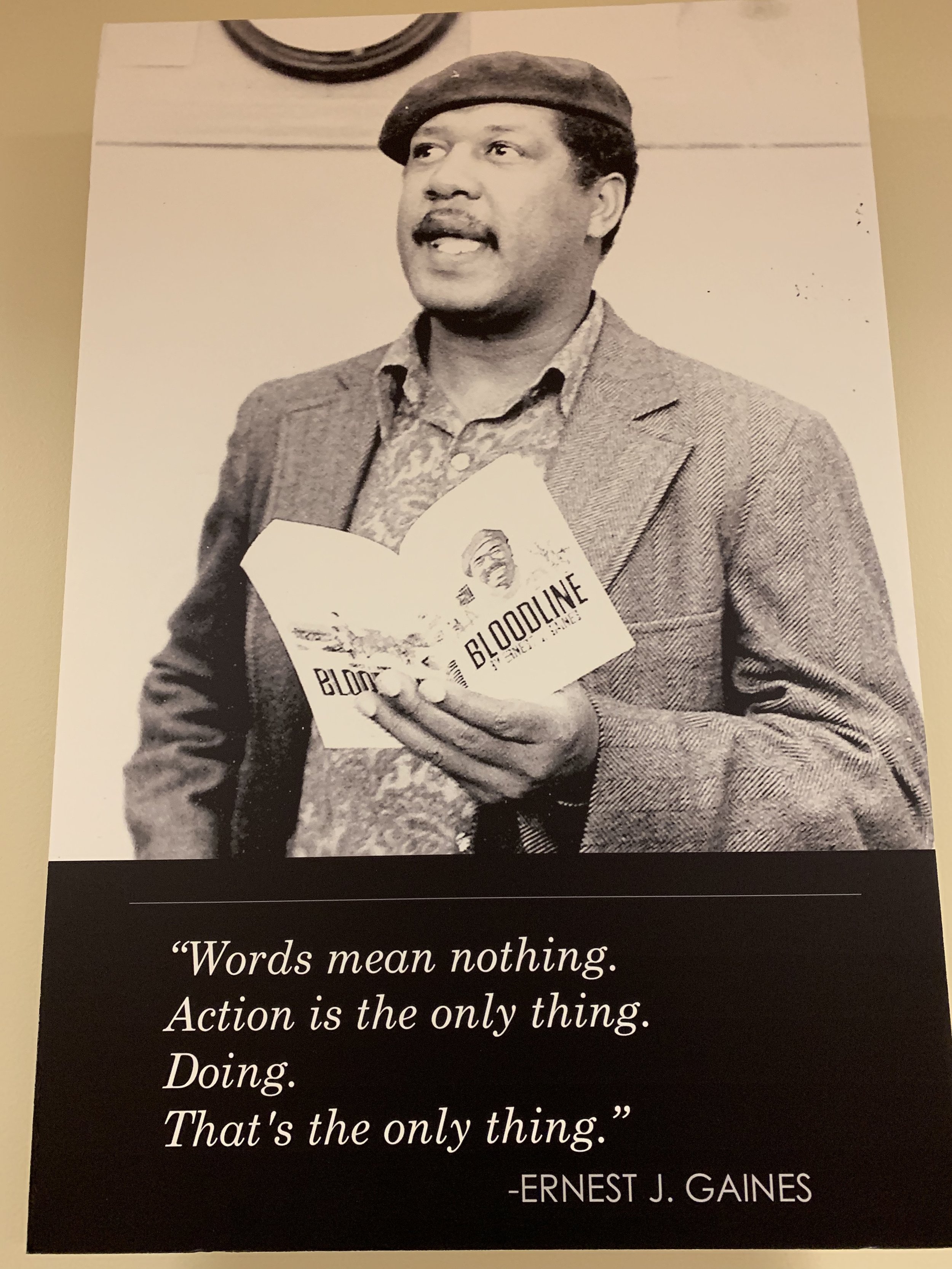

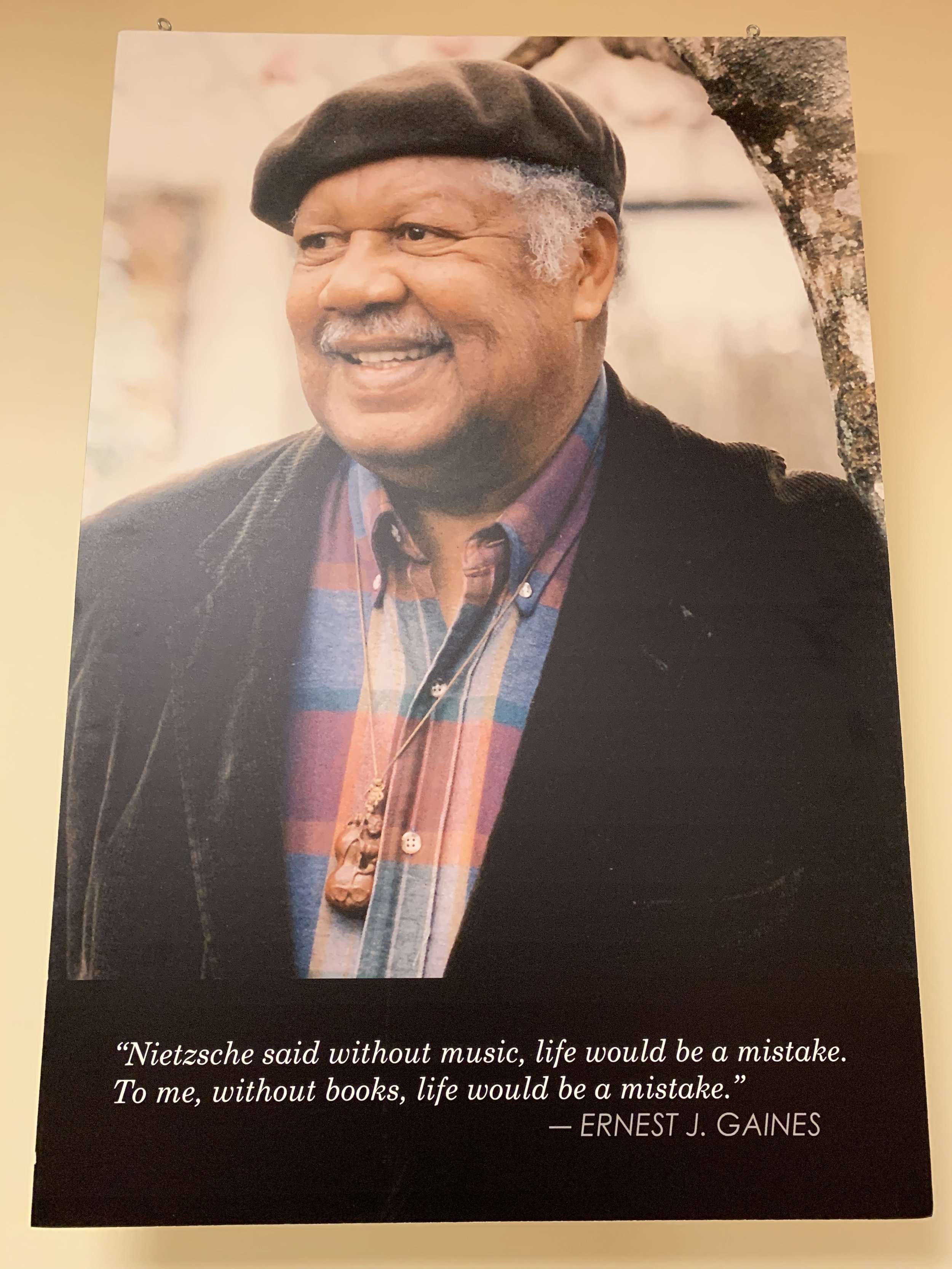

What truly made this novel come to life for many of us bookpackers, though, was meeting the man who put the story to paper. The one-in-a-lifetime experience of meeting Ernest J. Gaines in person and getting to discuss this novel and the art of writing with him was something that meant a great deal to me, personally. To be a writer with the opportunity to receive advice from someone so acclaimed was simply astounding. Gaines advice was overshadowed, though, when I began to realize that he did not just bring the story to life but was also making efforts to preserve the history from which the story derived.

The property on which Dr. Gaines lives was the very same plantation he grew up on and he has made many efforts to keep the land true to its roots. He has gone to lengths as great as moving the church, which also functioned as a schoolhouse, that inspired the church in which Grant taught onto his property, into his backyard, to keep it from getting demolished. Rather than get rid of a piece of history such as this, he has taken it into his own hands and kept up the maintenance of the building and the narrative it tells. Having taken a seat on the benches of the church, I felt A Lesson Before Dying become tangible and could almost see Grant behind the podium in the church with his Westcott ruler in hand, ready to smack any of his students brave enough to misbehave.

“Do I know what a man is? Do I know how a man is supposed to die? I’m still trying to figure out how a man should live.”

Not only did the setting of the book become tangible in walls of this church, but Grant’s feeling of confinement and desire to escape did as well. I could feel how the walls of the church and the surrounding town could become a type of prison in the mind of Grant, an inescapable life sentence to something seemingly mundane and undesirable. As he says himself, every day is about the same. He knows what his students will say, who will wear what, and who will go on to be somebody regardless of his influence on them. Grant, in living out his self-imposed Groundhog’s Day, finds that he has commitment only to maintaining the mundane life he leads.

This is not a feeling unique to Grant, as I’ve often found myself in a similar sort of rut with seemingly no escape. The routines of everyday life can quickly grow tiresome and, just as teaching grows mundane to Grant, being a student can seem just as mundane. Going to lecture after lecture only to hear professors rattle on about, more often than not, something they’ve already discussed countless times, gave me a decent idea of how Grant felt listening to his students rattle off the same few bible verses every morning. The overdone and outlived nature of every day leaves a person worn out beyond belief, hopelessly begging for a change and a sense of purpose being restored.

Grant and I, to an admittedly lesser degree, both receive this sense of purpose, whether or not we are reluctant to take it initially. Grant receives his sense of purpose from the impossible task he’d been given: teaching Jefferson how to be a man. In taking on this task, Grant is not only taken out of his rut of daily bible verses, he is also given the chance to make a change for someone else. The change is twofold, as both end up having a great influence on the other and, in the end, Grant is made a better man with a newfound sense of purpose and sense of self.

I, like Grant, have been pulled out of my rut by an impossible task: travelling to Louisiana with 12 complete strangers, visiting various historical sites, reading various historical works, and somehow making friends along the way. Much as Grant is apprehensive towards his task with Jefferson, I was apprehensive about this bookpacking experience. Before departure, there were countless times I contemplated dropping out of the course, sure that I wouldn’t enjoy the journey. Once the fateful day came and I was sitting on the plane, I thought about getting up and off as fast as possible. Routines weren’t meant to be broken, I thought. Scenario after scenario flew through my head but, against my better judgement, I fastened my seat belt. I’m glad I did.

Had I turned back around and let my own apprehension get the better of me, I would have missed out on some of the coolest experiences and some of the most amazing friendships. From going out sightseeing to staying in for hotel movie nights, strutting down Bourbon Street to strolling in the Garden District, and sunrise swims to midnight ice cream runs, I’ve made countless memories with my fellow bookpackers. Both having been stuck in our own ruts of mundane living, Grant and I were jarred back into motion by life-changing experiences. Grant, in choosing to continue his lessons with Jefferson, and I, in choosing not to hop on the first plane out of Louisiana, did what we did not think we could: we broke our routines and changed for the better.

“Yes, I told myself. It is finally over.”