Our first days away from our beloved New Orleans found us in Baton Rouge, sleepy thanks to Memorial Day, at a hotel next to the gorgeous Mississippi, where we were to read Ernest J. Gaines’s A Lesson Before Dying while exploring the State Capitol building and visiting the small town nearby where the novel was set. A Lesson Before Dying is about Grant, a young teacher grappling with the immense task of convincing Jefferson, a wrongfully convicted 21-year-old awaiting execution, of his own humanity—all under the hopeful eyes of a struggling community.

While reading this book, we had the privilege of immersing ourselves in the text by exploring the very places where the novel is set. We visited Point Coupée parish to see the prison cells where Jefferson would have had to live his final weeks—miserable little boxes, sealed by cruel metal bars and walls of bleak, flaking paint. Shockingly, this horrible place had only been retired as a prison in the 1980’s. The atmosphere of the prison was smothering, suffocating us due to its lack of air conditioning, and intimidating us with walls decorated with mold and wasp nests. Stepping into those cells, and having them close on us, trapping us inside, made Jefferson’s experience feel very real. I tried to stay light-hearted at the time, not allowing myself until much later in the day to reflect on the despair and helplessness that Jefferson must have felt in that cramped, hot cell. I found the arithmetic scribbled on the walls— “53 days left,” it said—quite disturbing, and I wanted to get out. It’s easy to forget that inhumane places like these still exist, that we still lock people up, reducing their freedom on this vast planet to about 4 by 8 feet of cement. And then I thought of Jefferson, sentenced for a crime he did not commit, and sent to this awful place with the belief embedded in him that he was not a human but a hog. This put Grant’s fear and hesitation into perspective—how do you transform someone who believes that they are as lowly as a hog, reducing themselves to eating on their knees with their hands behind their back, into someone who believes firmly in their own humanity? How do you convince someone to walk with their head held high to the electric chair? We all left that little prison—whether we revealed it or not in our outward disposition—uneasy and remorseful over the experience. I think we were all thinking of poor Jefferson and the inner tumult he must have been facing in that grim place. Visiting the prison made Jefferson’s ultimate transformation into a man even more astounding and impactful—I understood then what made him a hero.

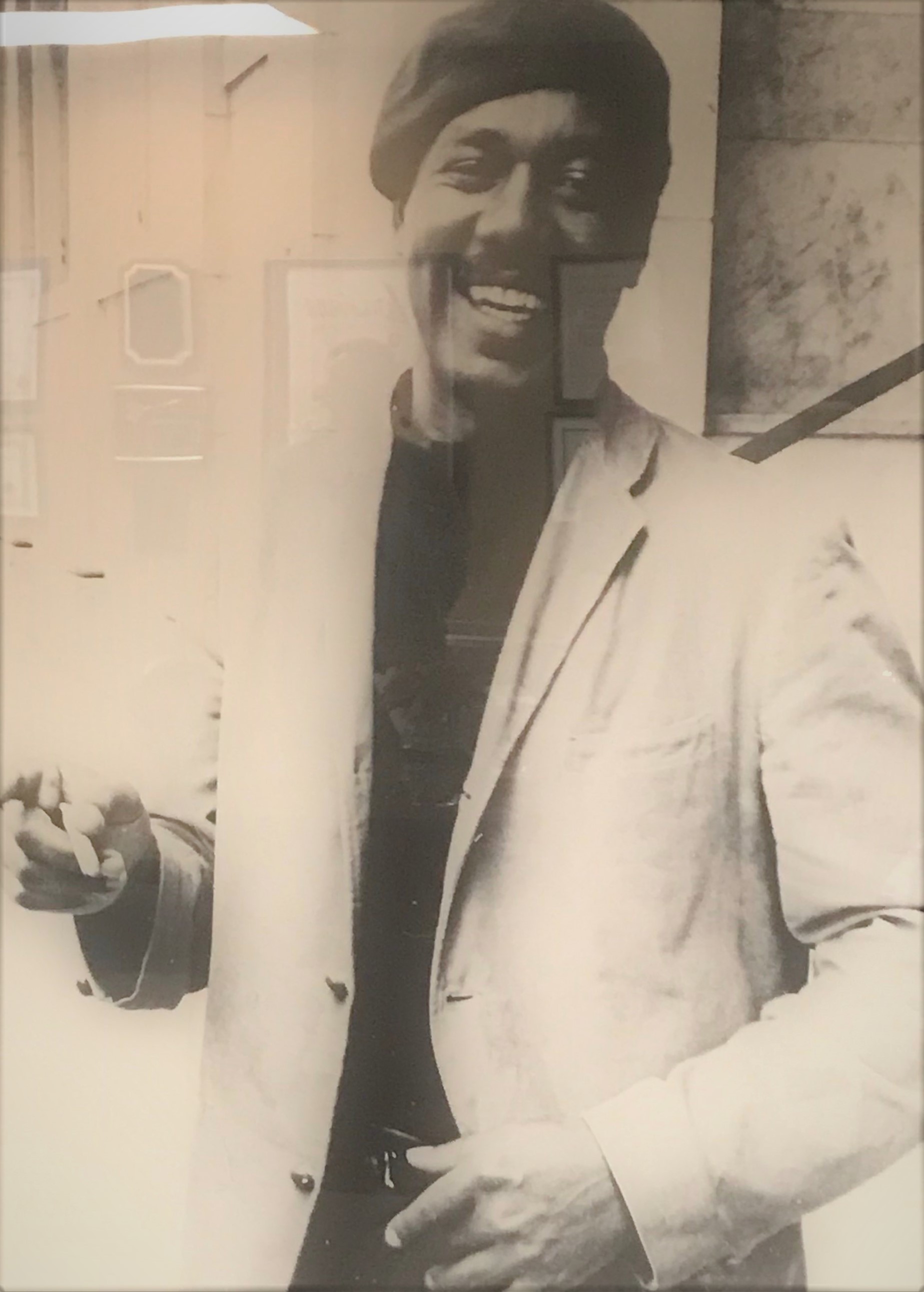

The next day, we were lucky enough to meet Dr. Ernest J. Gaines in his home on the False River. We asked him questions about A Lesson Before Dying, his path to becoming a writer, and—my favorite part—his relationship with his wife, Diane, who was constantly keeping him on track when his answers started to drift. It was a truly special experience, which helped me understand the characters and message in the novel more. Interestingly, Dr. Gaines shared that he never put himself fully into any one character. He also gave us insight into his decision to allow Reverend Ambrose, a somewhat difficult character to support when reading, to rise up at the end of the novel when he, not Grant, was at the execution. His decision showed that, though an educated man himself, Dr. Gaines seemed to value belief—in people, in community, in God, even—over cynicism. We would soon discover that even more as the woman in charge of his archives, Shalon, showed us all that Dr. Gaines had done for his community. She took us to the restored church where the fictional Grant taught the plantation children, where she explained the significance of sharecropping and the poor circumstances of its unfortunate participants.

Throughout this experience, it became clear that Dr. Gaines both like Grant and Reverend Ambrose in his contribution to his community and simultaneous faith in its future. As we explored the town, we noticed the disturbing remains of an unsavory history—a celebratory statue of a confederate soldier, proudly waving his flags, and a memorial to a Native American, described on his plaque as a “savage.” Perhaps even more disturbing was the consistent erasure of black history, the history of those whose blood, sweat, and tears built that very town. Dr. Gaines and his colleagues are on the front lines, doing everything they can to prevent their history from disappearing. Shalon took us to the plantation graveyard—a tiny plot of land surrounded by thick grass, which was the only place plantation workers were allowed to bury their dead—to show us first hand how easy it was for black history to be erased and how important it was to maintain it. The graveyard had almost been demolished by tractors, if Dr. Gaines himself had not helped save and preserve it. Shalon raised a thought-provoking question to the group: “what makes a graveyard? How do you know you’re at a graveyard?” We hesitated to reply because we knew the answer wasn’t pretty, so she repeated the question. I eventually responded, “headstones… graves” and she confirmed; plantation workers didn’t have the money to afford marble headstones, relying instead on impermanent organic materials like wooden crosses to mark the graves of their loved ones, which resulted in the decimation of their burial sites. People who didn’t know the area would carelessly build over these graveyards without a second thought. Most heartbreaking is that Dr. Gaines’s beloved aunt, who had never walked her entire life but had to drag herself on the ground all the while raising a flock of children, is buried somewhere in that patch of land in an unmarked grave—dear to so many and so strong, yet lost somewhere in the dirt. I thought about how I had taken for granted the simple privilege of knowing where my loved ones were buried, to have a place to visit them, to honor them. The idea that so many had that opportunity stolen from them made me angry and remorseful. We left the graveyard carefully, avoiding large spiders and itchy plants, ruminating on what Shalon had told us. She had also explained how sharecroppers were essentially trapped in their “jobs,” as they weren’t paid in US dollars but instead in currency specific to that plantation, which they could only use at the local plantation store. It’s with these stories that I began to relate with Grant and his former teacher Mr. Antoine in their utter cynicism—they were surrounded by the constant reminder of slavery and the notion that it hadn’t ended, just simply taken another name. I’m sure that Dr. Gaines felt similarly in his youth and perhaps even now, so I only admired him more for never ceasing to write about hope. Where Mr. Antoine died pessimistic about the fate of his community, Ernest Gaines lives like the reformed Grant, perhaps not entirely relieved of cynicism, but never ceasing. Like Grant would continue to teach the story of Jefferson, Dr. Gaines continues to tell the stories of the brave people of his community and teach the history he refuses to let be erased.

Our final discussion on A Lesson Before Dying was an emotional one. Though about a specific community facing a gut-wrenching tragedy, this novel carries a universal message. Ultimately, it is about allowing oneself to be loved and believing in ones humanity. It is about finding hope and happiness, not in your material possessions or tangible accomplishments, but in the people that love you. That is how Jefferson walked to that chair a man. Wrapping up our discussion, our professor, Andrew, left us with the Shakespearean sonnet he goes to when he feels he needs this very message. Coincidentally, I recited this sonnet years ago in theatre but realized when Andrew spoke it that I had never truly understood it. As I looked around at my new friends and a professor that truly believed in me, I finally got it. I am good and human and worthy because of them and because of my friends back home and because of my family. Without much further ado, I leave you with this:

“When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

(Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

”