France’s streets sing with the echoes of history.

Just a single ceiling in the Palace of Versailles

When our class visits Versailles, it feels like stepping back in time. Every room is furnished with lavish luxuries, including magnificent chandeliers and marble columns; at every turn, we walk through doorways dripping with gold. If I were a peasant in eighteenth-century France, I would’ve probably fallen at the feet of the “jewels and silks and powder and splendour” of the King, Queen, and their Court. Like A Tale of Two Cities’ mender of roads, I would’ve been overwhelmed by their incredible elegance and glamor, yelling “Long live the King!” in unrestrained awe.

In the Place de La Bastille, metal markers outline the shape of the old fortress. It’s smaller than I thought it would be - in paintings, it seems like a hulking mass looming over the city from a distance. In person, I suddenly understand how crowds could’ve rushed at the royal fortress and dismantled it brick by brick. I realize how their riotous anger would’ve caught on like wildfire, creating a “remorseless sea of turbulently swaying shapes, voices of vengeance, and faces hardened in the furnaces of suffering,” just as Dickens describes in his novel.

Nowhere is the cry of history as strong as in the Place de la Révolution, the former site of the guillotine. On the day that we visit it, the sky is achingly bright. I imagine the condemned squinting in the sun as they mount the scaffold, surrounded by a tumultuous crowd. I think of Sydney Carton and the untold numbers of men like him, good people killed by the bloodthirsty Revolution.

How do we honor this storied past?

An outline of the old royal fortress at the Place de la Bastille

First, we remember history’s participants. We focus on the humanity of both sides - by reading texts like A Tale of Two Cities and Les Misérables, we understand how appalling social conditions sparked the people’s well-founded anger, whether it was the revolutionaries of 1789 or the insurgents of the 1832 barricade. Yet Darnay’s story in A Tale of Two Cities also creates sympathy for those aristocrats whose only crime was a tie to the Second Estate. When we stand where Lucie did so that Darnay could see his wife from prison, faithfully waiting there no matter the day or the weather, we see the cruelty of the couple’s separation. By acknowledging that there is no side in history that was absolutely right, we are better able to understand the stories of our predecessors.

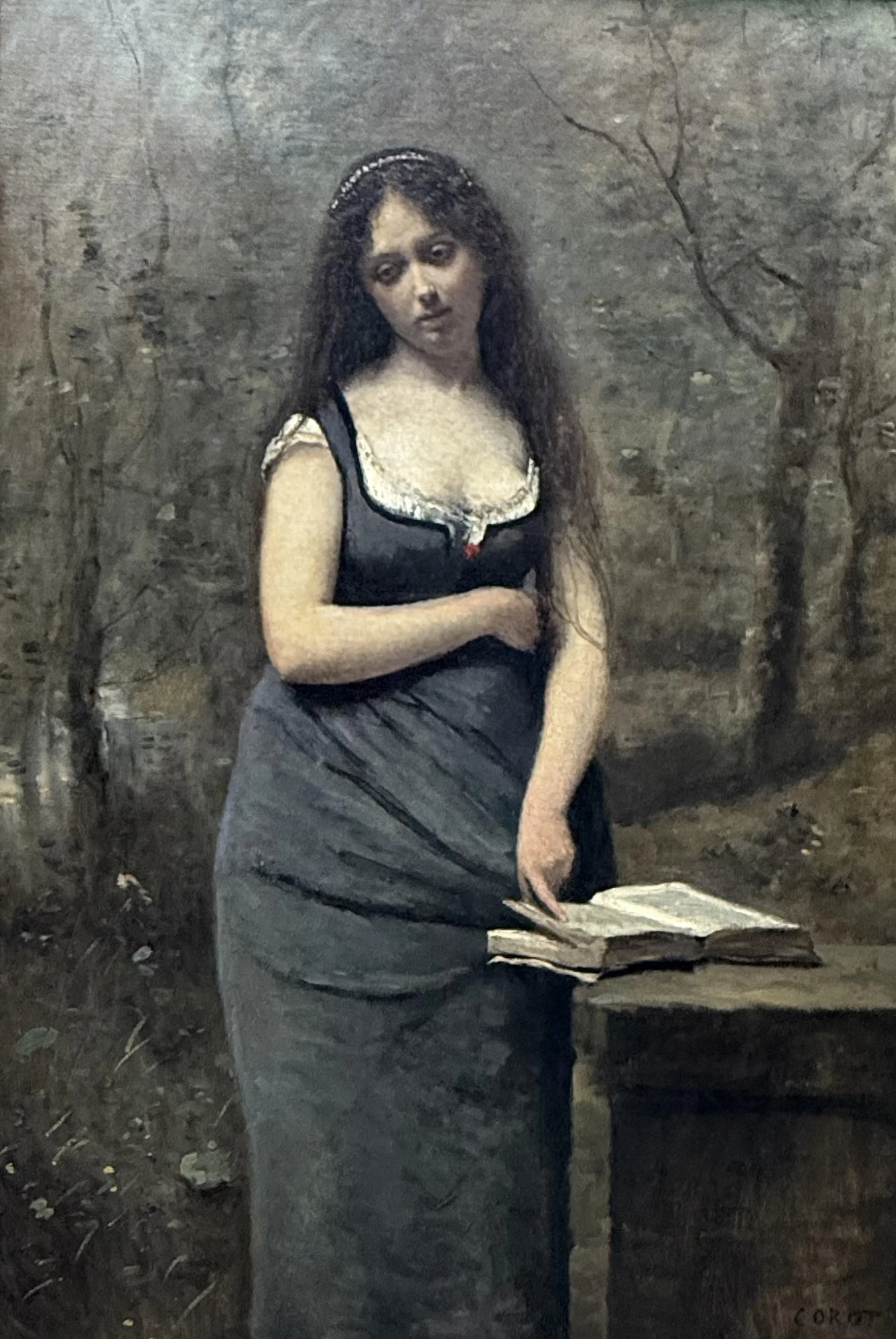

We must also honor those who history often forgets. At the Musée Carnavalet, I learned how women were an active part of the revolutionary dynamic despite being left out of most revolutionary iconography. According to historian Clyde Plumauzille, women played the role of “firebrands,” triggering riots during shortages, and even took part in Assembly debates from the gallery. At the Conciergerie, our class was introduced to figures like Olympe de Gouges, who wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in response to 1789’s Declaration of the Rights of Man. Even women like Lucie Manette, a character often dismissed as people-pleasing and passive, held whole families together. At the trial to determine her husband’s fate, Lucie gives Charles Darnay an expression “so sustaining, so encouraging… so courageous for his sake, that it called the healthy blood into his face.” I love this image because it highlights Lucie’s quiet strength in the face of unspeakable horror. It’s easy to write off women like her as aimless bystanders, but they, too, shaped the dynamic of history.

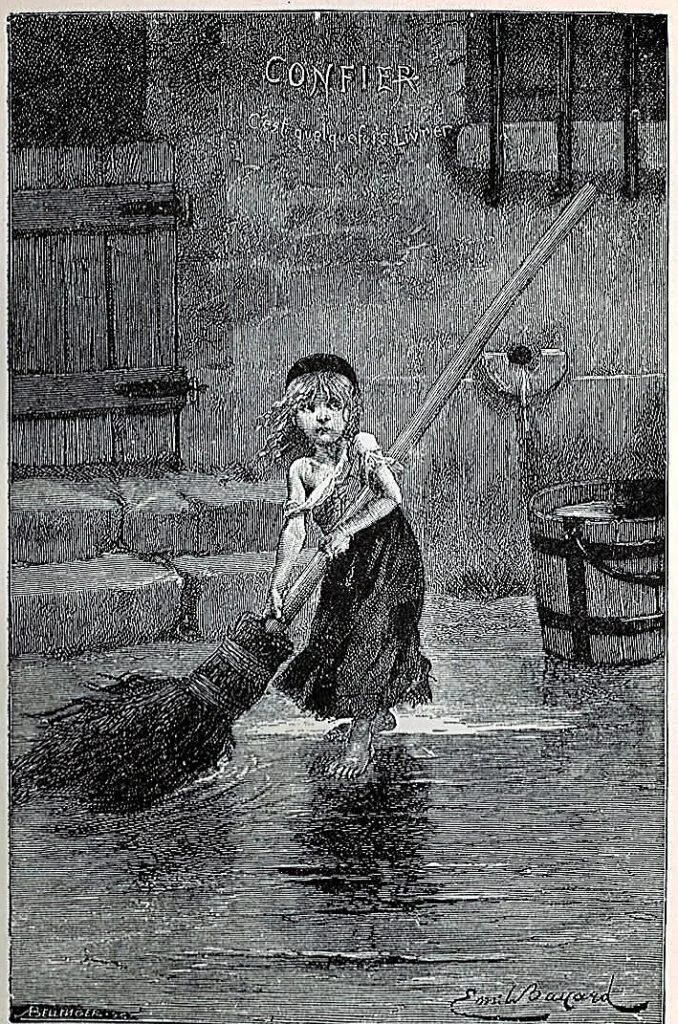

Yet our Lucies and Cosettes also remind us of the future these revolutionaries fought for. In both A Tale of Two Cities and Les Misérables, the protagonists’ visions of the future were not about who won or lost. They weren’t about a total overthrow of societal order or the extinction of an entire class. At the foot of the scaffold, Sydney sees “the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous and happy… I see that I hold a sanctuary in their hearts, and in the hearts of their descendants, generations hence.” This beautiful image is humble and personal. It isn’t grand - Sydney doesn’t try to save the whole of France - but it envisions a family that no longer lives in fear. The future Sydney sacrifices himself for is one of humility and tranquility, of quiet joy and hopeful strength. On her wedding day, Cosette realizes that her “sorrows, sleeplessness, tears, anguish, terrors, despair… were making yet more blissful the coming moments of bliss.” Maybe this is the whole point: maybe people fight so that past sufferings can lead to present satisfaction. They fight for Lucie, happy with her husband and children, and Cosette, content in Marius' arms.

Even Enjolras, in his grandiose speech at the barricade, speaks of this forthcoming joy:

“Light! Light! Everything comes from light, and returns to it. Citizens, the nineteenth century is a great century, but the twentieth century will be a happy one. Nothing like the history of old - not any more. There’ll be no reason then to fear.... Brothers, he who dies here dies in the radiance of the future, and we go to a grave pervaded through and through by the light of dawn.”

If Hugo and Dickens were to bookpack with us, accompanying our class to the sites that they described in their novels, I think they’d be pleased. Imagine their joy to see children playing at the site of the old Bastille, totally unaware of the bloody chaos that once took place. Imagine how wonderful it would be to watch happy crowds at the cafe in Les Halles where the barricade once stood. Wouldn’t Hugo be so bemused to see people now shuffling through the sewer museum and buying sewer rat soft toys as souvenirs?

The future is still imperfect. Dickens’ opening line - “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” - is absolutely true today. As we’ve explored London and Paris through history’s eyes, it’s been such a gift to realize how far this world has come, while also acknowledging the work we still need to do. It’s been an even greater privilege to discuss these topics alongside nine people who have been endlessly open, thoughtful, and kind. As I see families picnicking at the Champ de Mars and couples strolling quietly along the banks of the Seine, I know the future I fight for.

I hope we all do.

A final sunset along the Seine.