Our explorations so far have focused on the intersection between book and place, but Les Misérables is a tale that transcends time and space. To prove it, we went to the Louvre and searched its collection for each character’s painted counterpart.

Here’s a catalogue of our beloved crew, as seen through centuries of European art:

Javert | The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of his Sons, Jacques-Louis David

In the corner of this painting, we see Brutus half-hidden in the shadows, his face a mask of grim devotion. Behind him lies the body of one of his sons, who Brutus had beheaded for conspiring against the Republic. Brutus’ pose is tense and agitated - here, he is forced to choose between loyalty and love.

The parallels between this Roman consul and Javert are clear: both are rigid in their devotion to justice and legalism. Javert’s agony after letting Valjean go mirrors Brutus’ agitation as he watches his family mourn. Both men test the extent of their humanity. On that bridge over the Seine, Javert suddenly realizes how terrible it is that “beneath your torso of bronze you have something absurd and unruly that is almost like a heart.” I’m sure Brutus is reckoning with the same dreadful feeling as he tests how far he will go for the sake of his country. Brutus loses his sons and Javert, unable to cope with his changed conscience, loses his life.

Fantine | The Burial of Atala, Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson

The placard next to the painting tells us that Atala is the fiancée of a Native American man called Chactas, who hugs her legs. She has poisoned herself in order to preserve her vow of chastity. Through the mouth of the cave we see a cross in the distance and the soft glow of light. The description to the left of the painting tells us that, through the cross bathed in light, the scene’s “horror and sadness are mitigated by the Christian belief in salvation after death.”

Fantine’s last moments are not so peaceful. Yet like Atala, Fantine also serves as a figure of purity. Despite her past, when Jean Valjean first meets her, he says that “you’ve never ceased to be virtuous and holy in the sight of God.” Valjean, like the priest in this painting, gently takes care of Fantine’s body after her death, tidying her hair and closing her eyes. Just as we see with the light in this picture, Fantine’s face is also “strangely illuminated.” For both Atala and Fantine, our consolation is that they will be saved from their earthly suffering in heaven.

Marius | Daphnis et Chloé, François Gérard

Let’s be honest: the man in this painting looks exactly like the kind of guy who’d say something like “If there were not someone who loved, the sun would be extinguished” (yes, that is an authentic Marius quote). In this painting, Daphnis and his lover, Chloé, are peaceful, radiant, and resplendent in their love. This scene reminds me of when Marius meets with Cosette in her garden. Look at the painting’s bright rays of sun! Look at its lush foliage and lovely colors. It looks exactly like how the couple would see their world together.

Throughout the novel, Marius often goes to extremes. He changes from a loyal royalist to a defiant Bonapartist in memory of his father. One day, he’s in raptures over Cosette; the next, he’s risking his life on the barricade because he can't bear to live without her. It's hard to understand Marius’ ideology sometimes because the majority of his motivations are characterized by love - love for his father, love for his partner, and love for his friends. That is how he operates, and that is how we see him in this painting. Marius: a man in love.

“Marius was at Cosette’s side. Never had the sky been starrier or more spellbinding, the trees more tremulous, the plant smells more pervasive. Never had the birds fallen asleep among the leaves with a sweeter sound. Never had all the harmonics of cosmic serenity better answered the inward music of love.”

Gavroche | The Wounded Drummer Boy, François Bouchot

Gavroche, the little gamin, is present in every brushstroke of this painting. According to the Louvre’s description, this “drummer boy” could have been the real-life Joseph Bara, a fourteen-year-old volunteer in the French Revolutionary Army. He was killed by Vendean royalists and became a republican martyr.

The drummer boy’s youthful innocence is etched into the canvas, his final expression soft and peaceful. His young age is a testament to the fighting’s brutality. Gavroche, like the drummer boy, is the epitome of revolutionary spirit. Both boys illustrate the battle’s costs through their tragic deaths: for example, when Gavroche is shot, “The whole barricade gave a cry.”

Gavroche may not be a drummer boy, but he goes down singing. This “great little soul” gives strength to the rest of the barricade.

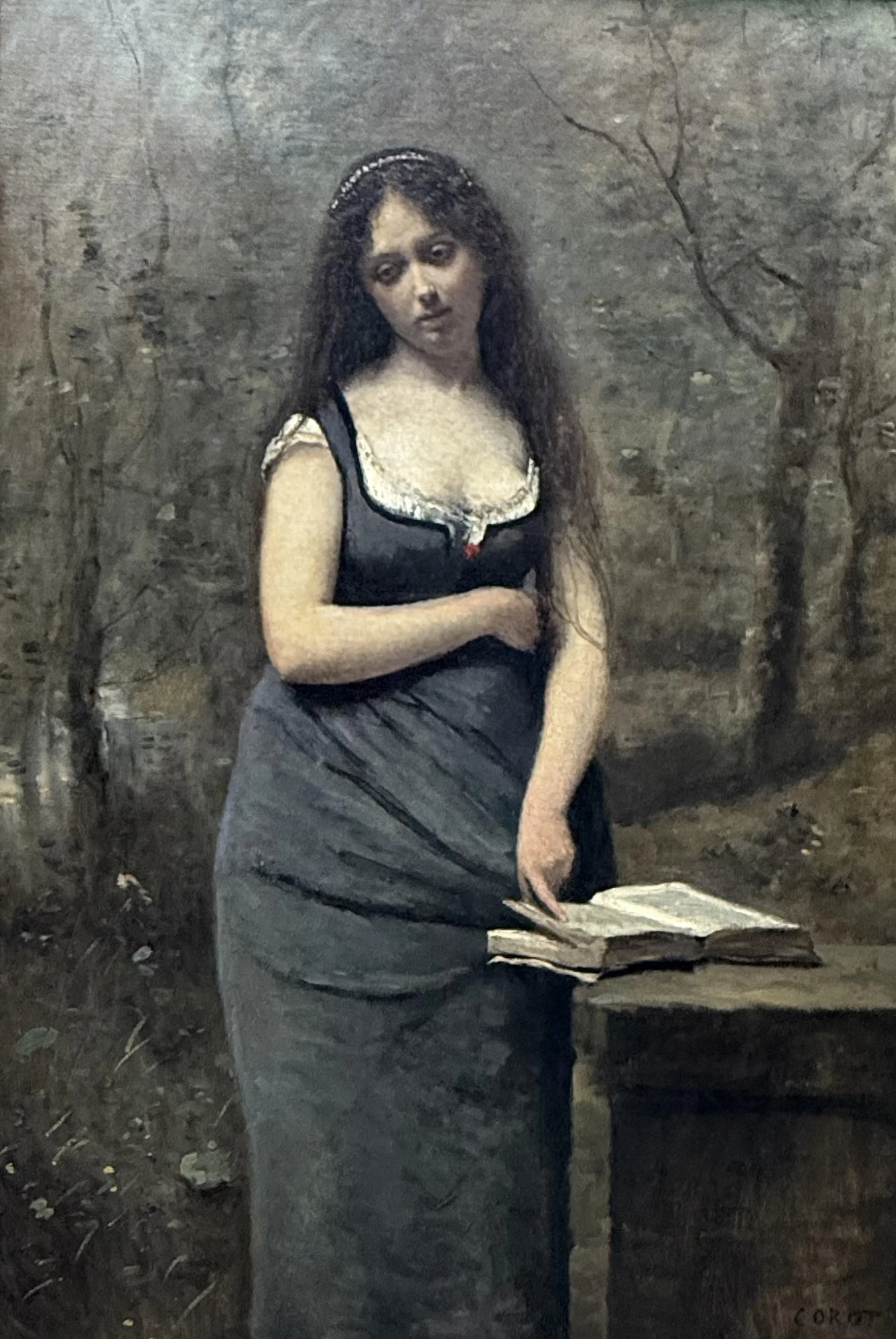

Éponine | Velléda, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot

This girl’s plain clothes and pained expression make me immediately think of Éponine. She looks down rather than at the viewer, her dark eyes mournful. Her eyes are dull and her hair long and unkempt. The dark, wintry background reminds me of the cold Gorbeau tenement, which Hugo describes as “squalid, dark, [and] sordid.”

The girl’s index finger rests listlessly on an open book. When I saw it, I thought of how sad Éponine seems when she boasts that she knows how to write. She reads and writes fluently, to be sure, but she shows off as if she is trying to prove that she is not as pitiful as she seems. “There’s no spelling mistakes,” she tells Marius. “You can look. We’ve had some education, my sister and me. We haven’t always been the way we are now.”

Maybe the girl in this painting feels the same shame.

Enjolras | Wounded Roman Soldier, Jean-Germain Drouais

The soldier’s gaze is fierce. His hand covers a bloody cut. His sword lies by his side, ready to be picked up again; whoever this soldier is, he has not given up. Though he is wounded, he is ready to fight.

I see Enjolras here, a man with “only one passion: rightfulness.” Indeed, like this Roman soldier, Enjolras won’t back down from what he believes in. When Enjolras is about to be killed by a throng of soldiers and guardsmen, he faces them “with a proud gaze, head held high, with that stump of a weapon in his hand.” I picture him with the same expression as the wounded Roman soldier here. These men will never give up their honor or courage. They will always look their enemies in the eye.

“‘Who goes there?’

At the same time could be heard the clatter of guns being readied.

Enjolras replied in a proud, ringing tone, ‘The French Revolution!’”

Cosette | Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci

This is the only picture I've included with other people in it, mainly because I wanted to show you that the Mona Lisa is packed. Tourists from all around the world clamor to take her picture. She is adored by everyone for reasons nobody can really articulate. She has become the icon of the Louvre in the same way that Cosette has become the icon of Les Misérables.

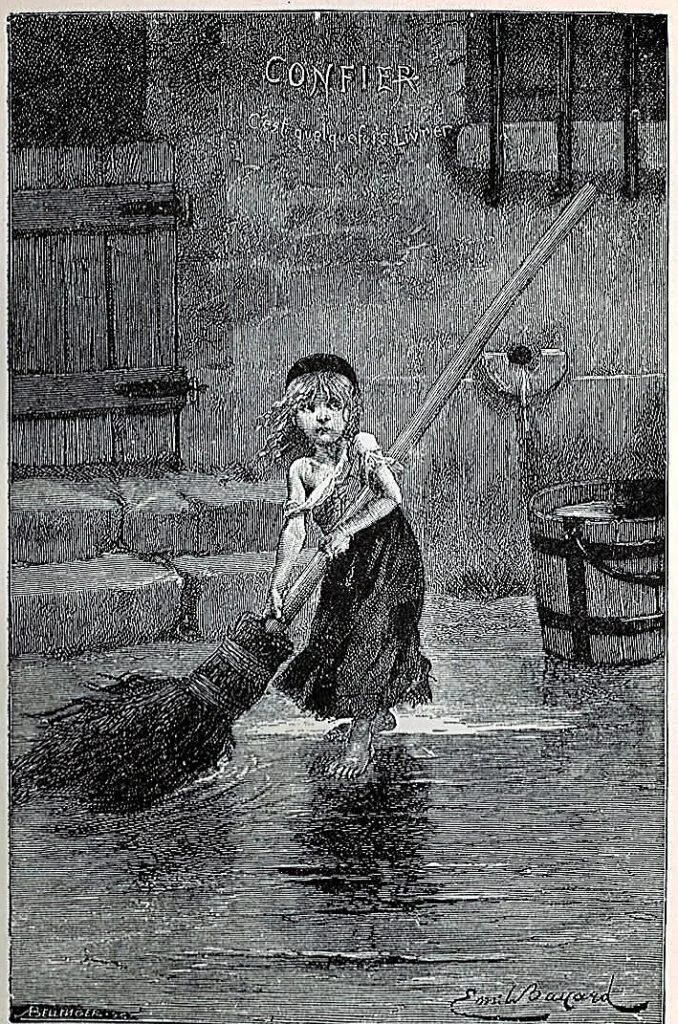

Bayard’s Cosette Sweeping - not in the Louvre but often found on book covers and musical posters. Les Mis’ own Mona Lisa.

Both women are beautiful, both are popular, both are loved by all. For better or for worse, they have become the faces of something much larger than themselves. Whether people read Les Misérables for the little girl on the cover or come to the Louvre for the woman with the mysterious smile, I hope they find so much more than they ever hoped for.

Jean Valjean

There are quite a few paintings that remind me of our protagonist’s chief characteristics: the tenderness in the elderly gentleman’s face in Portrait of an Old Man and a Boy, the heroic dedication of the brown-haired man in The Deluge, the peaceful solitude of the figure in Sunset in Chevrier…

But I found that Jean Valjean most resembles us, the visitors at the Louvre. Like us at the museum, Valjean sees the heights and depths of humanity. Yet while we see it through paintings, he sees it through his own experiences. When he meets the bishop, for example, Valjean encounters the best of men; when he sees the exploitation of Cosette, the wickedness of Paris’ criminal underbelly, and the brutality of the barricade, he sees the very worst. Like us, Valjean is often on the outside looking in. He observes others from a distance, feeling as separated as we do from the events of these paintings: for most of the years he spends with Cosette, Valjean “was concealing his name, concealing his identity, concealing his age” in order to protect his family from his past.

There’s parts of Valjean that resonate with all of us, whether that be his complicated backstory, his changed personality, or his ongoing journey to redemption. As museum-goers, we get to see how the story and characters of Les Misérables are reflected across countless places and periods, from fifteenth-century tempera paintings to our contemporary experiences. In both the Louvre and Les Mis, we see emotion, love, glory, pain, light, and darkness - we see every expression of our shared humanity.