Upon reading the title of this blog, one may assume that it will cover the story of Cosette and Marius, which is the central love story in the second half of the novel. Maybe it will be about Éponine’s unrequited love for Marius throughout Marius’s pursuit of Cosette. One may think of Fantine and her endless love for her daughter Cosette, and the sad and tragic end to her story. It could cover Jean Valjean, a man who never truly experienced love until he raised Cosette as essentially his daughter. These are many of the things we think of when we think of Les Misérables and stories of love. However, this blog will be centered around one small, tender moment from early on in the novel that could easily be forgotten after absorbing 1300 pages of the grand, epic story of Les Misérables.

My personal favorite part of Les Misérables, the one page that has stuck in my mind the most after reading the novel, was the description of Monsieur Myriel, or “Monseigneur Bienvenu”, the bishop of Digne’s last few years of life before his passing. This comes from Chapter Four, Book Five, Part One. The chapter revealed that Monsieur Myriel had died at the age of eighty-two, while Jean Valjean was creating his new life as “Pere Madeleine” in Montreuil-sur-Mer. It also revealed that Monsieur Myriel was blind in his last few years of life. Hugo describes him as having been “contentedly blind”, as he had the company of his sister. What follows is an incredible beautiful description of love, of how Monsieur Myriel’s reliance on his sister, and in turn her reliance on Monsieur Myriel, showed how much love they had for each other, that although he had lost his sight, Monsieur Myriel did not truly lose anything because he could feel the love of his sister through her presence and her actions.

“Incidentally, let us say that on this earth where nothing is perfect, to be blind and to be loved is in fact one of the most strangely exquisite forms of happiness.”

Hugo writes expertly and profoundly on the weight and power of love and of feeling loved, how it prevails over any negative circumstance or physical affliction. Despite his deteriorating physical condition and the loss of one of his five senses, Monsieur Myriel is described as being at his happiest, at his most content, at complete peace, because he knew he was loved. Of all of Hugo’s descriptions of love throughout the many pages of this novel, nothing was quite as touching and affecting as this one very short description of the end of Monsieur Myriel’s life.

Throughout the four weeks we spent in London and Paris, my mind kept coming back to this passage. In particular, I thought of this moment a lot during week one of the class, which we spent in London. I was feeling more homesick than I would have liked to admit, and I found myself missing family and friends much more than I expected to.

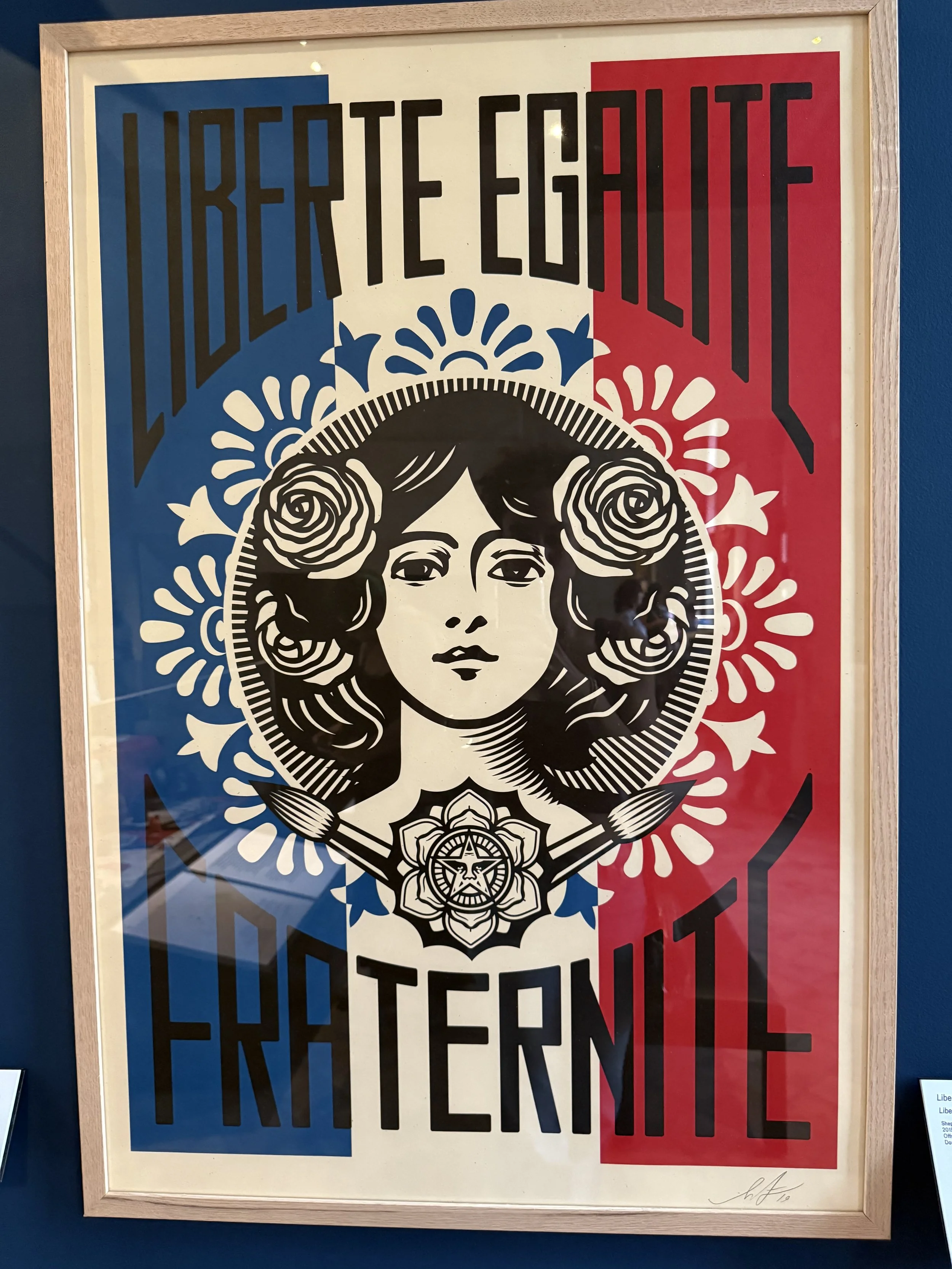

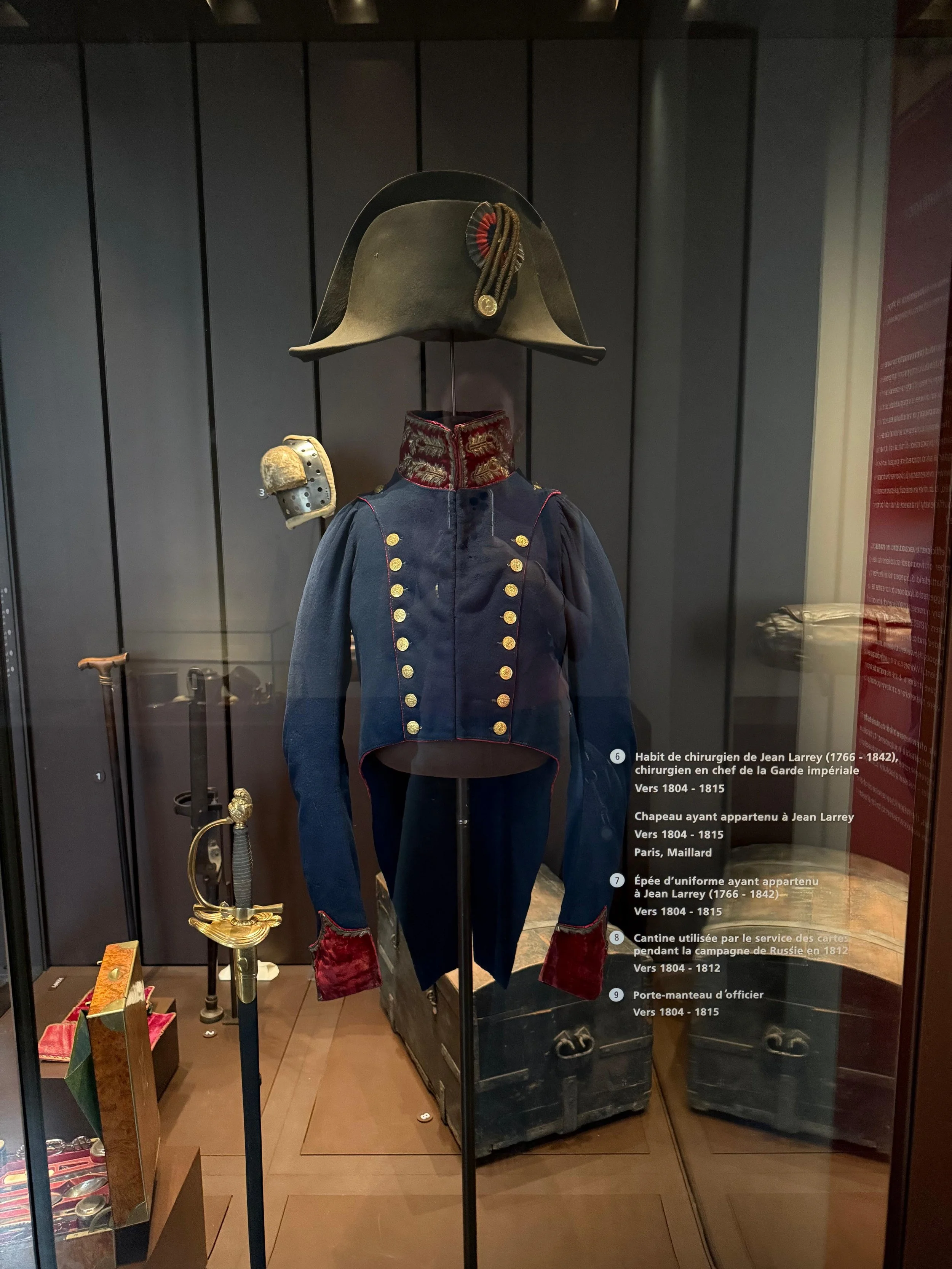

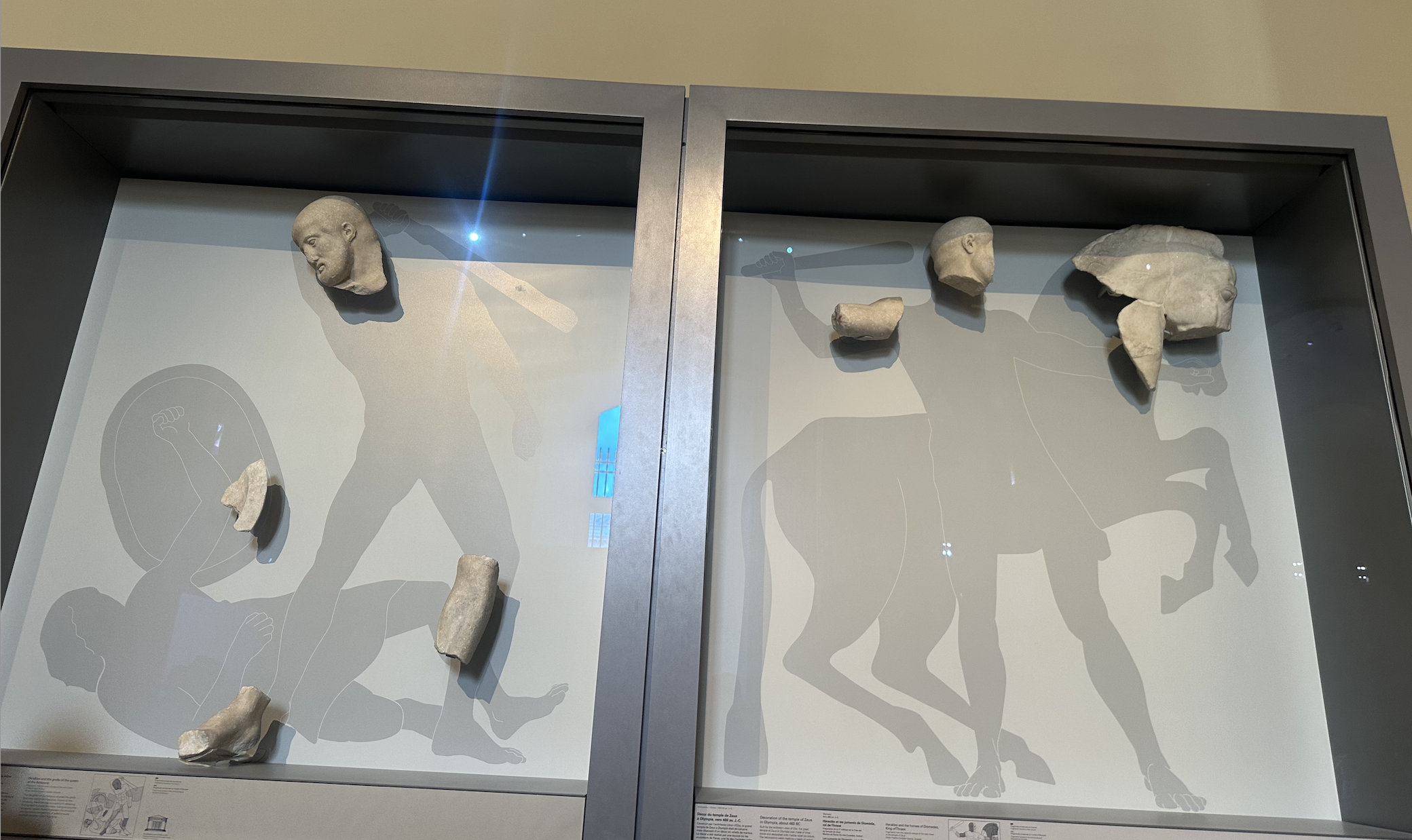

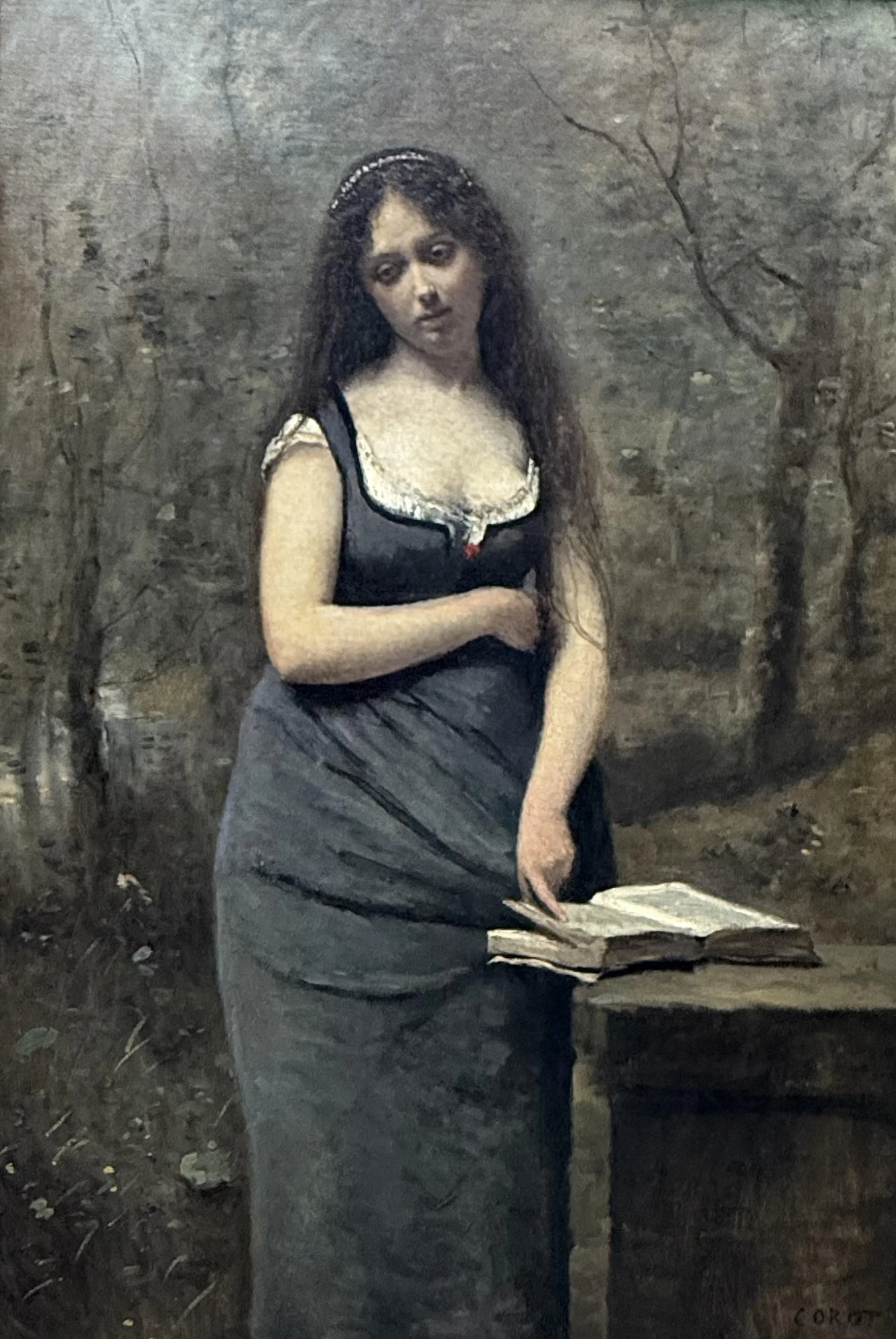

Throughout our explorations of London and Paris, every time we experienced something new, I thought of the people in my life who would have loved those experiences, and thought of how great it would be to be there again with them. As we walked through Borough Market in London, I thought of my foodiest friends who would have loved trying all of the different food stalls with me, and of my family who influenced me to love food more than almost anything. As we watched the stage production of Les Misérables, I thought of my friends who love musical theater, and how excited they would have been to sit with me and enjoy the show. As I walked into a new random bakery in Paris nearly every day, I thought of a friend who loves baking and trying new baked goods who would have appreciated the boulangeries even more than I did. As I walked through The Louvre, I thought of a friend with a passion for art history who would have had a greater level of appreciation and understanding for the endless walls of art than I ever could.

During these experiences and all of these thoughts and reminders of people in my life, I kept coming back to this passage about Monsieur Myriel. I realized that with every new experience I had that made me think of someone new, I felt their love with me, even though I couldn’t see them. I realized what a privilege it is to miss people. There’s a certain magic to walking through two new countries and having nearly every new experience remind me of someone who would love it even more than I would, and make me want to come back with them. More than a source of sadness or homesickness, I realized that thinking of people elevated these experiences for me, and made them all the more special.

“The supreme happiness of life is the conviction that you are loved, loved for yourself, better still, loved despite yourself”