From dangerous swamp land turned to crowded streets, New Orleans has survived disease, plague, hurricanes, floods, fires, and its constant battle with natural decay from its subtropical climate. In its near three hundred years, New Orleans has consistently entertained death as a part of its culture. With an extremely difficult terrain and Catholicism guiding the visual, visceral, and creative elements of Southern Gothic traditions, the people of New Orleans constructed great cemeteries with elaborate raised tombs. These cemeteries would become so overcrowded in their time, that they would push the boundaries of their limits, often stretching far beyond their intended walls. Years and years of development and decay have condensed these expansive “cities of the dead” into what they are today; impressive icons of generations lost.

New Orleans’ high water table makes common burial practices impossible. With the soil already heavily saturated with water and New Orleans’ insatiable rain, buried caskets would often rise from the ground. This dilemma was met with New Orleans’ Catholic traditions that gave birth to the intricate tombs, mausoleums, and statues that have made their cemeteries famous.

Within their years shared in New Orleans, European traditions and African religious practices blended together in the celebration of death. Jazz funerals, often given for members of social clubs or highly-esteemed members of the community, are understood as funerals with a parade processional that include music, dancing, and costumes. These funerals follow the family of the deceased from the funeral home to the cemetery. A band follows behind, along with a "second line," or members of the community who wish to pay their respects and celebrate the deceased.

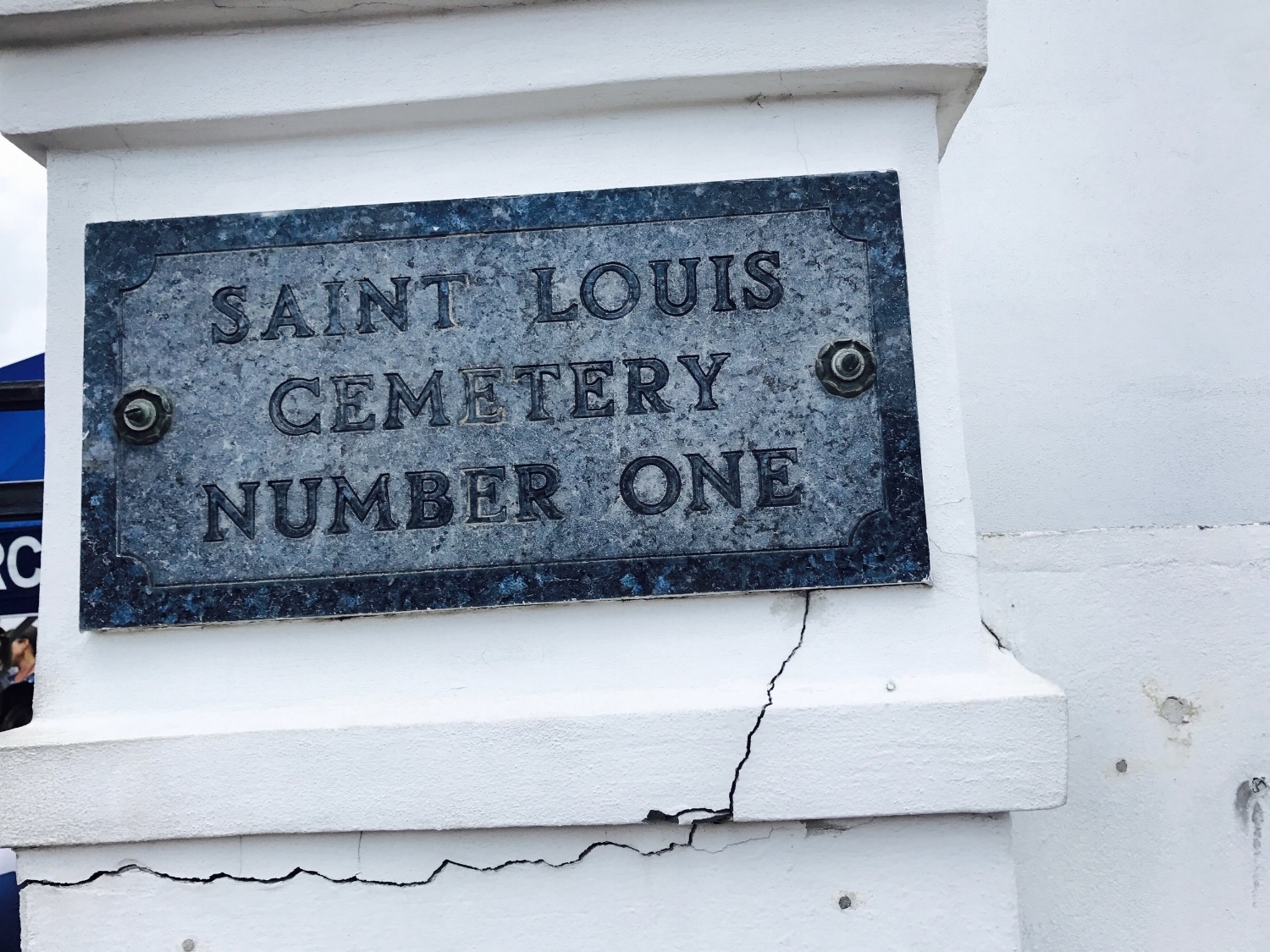

We visited New Orleans’ most famous cemetery, Saint Louis Cemetery Number One, on a bright, sunny day. The clouds had all moved from the sky, allowing the sun to reflect off of the chipping, white paint of the tombs. We walked around with our tour guide, admiring the crippled bricks, crumbled marble, and rusted iron fences that surrounded each ornate crypt. We admired the legendary tomb of the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans, Marie Laveau. Her tomb, marked with “X’s,” is still visited today by hopefuls who wish to make offerings to the Voodoo Queen for blessings in return. The cemetery is still active, welcoming those family members that have lineages entombed there – and of course, Nicholas Cage, who has built his own pyramid-shaped crypt, believing, he too, deserves some piece of New Orleans’ afterlife. Wouldn't we all like to believe we're that special?

With Anne Rice’s vampire novel, Interview with the Vampire, still in our hands, we strolled through the Garden District and into Lafayette Cemetery Number One. The threat of rain hung heavy in the clouds as we walked through sticky, mudded pathways. A place where death had become celebrated, discussed, and respected, New Orleans was the perfect setting for vampires to lurk. We imagined Rice’s young vampire, Claudia, prowling for her victims there as we meandered the thin alleys between the raised tombs. We entertained the thought of Claudia preying on those cemetery dwellers unfortunate enough to be caught in her path.

“And she asked to enter the cemetery of the suburb city of Lafayette and there roam the high marble tombs in search of those desperate men who, having no place else to sleep, spend what little they have on a bottle of wine, and crawl into a rotting vault.”