As an English Literature major at the University of Southern California, I have been taught to read beyond the surface and to explore the text, but I have never been so encouraged to bring those analytical skills into the physical world. Bookpacking challenged me to bring the hands-on learning approach to a genre of study that does not venture into the physical world much. Bookpacking became an adventure, bringing out a group of English majors into a contextual space. We broke free of our typical roles – locked away reading – using those books as a map to explore where the physical and the metaphysical of the text meet.

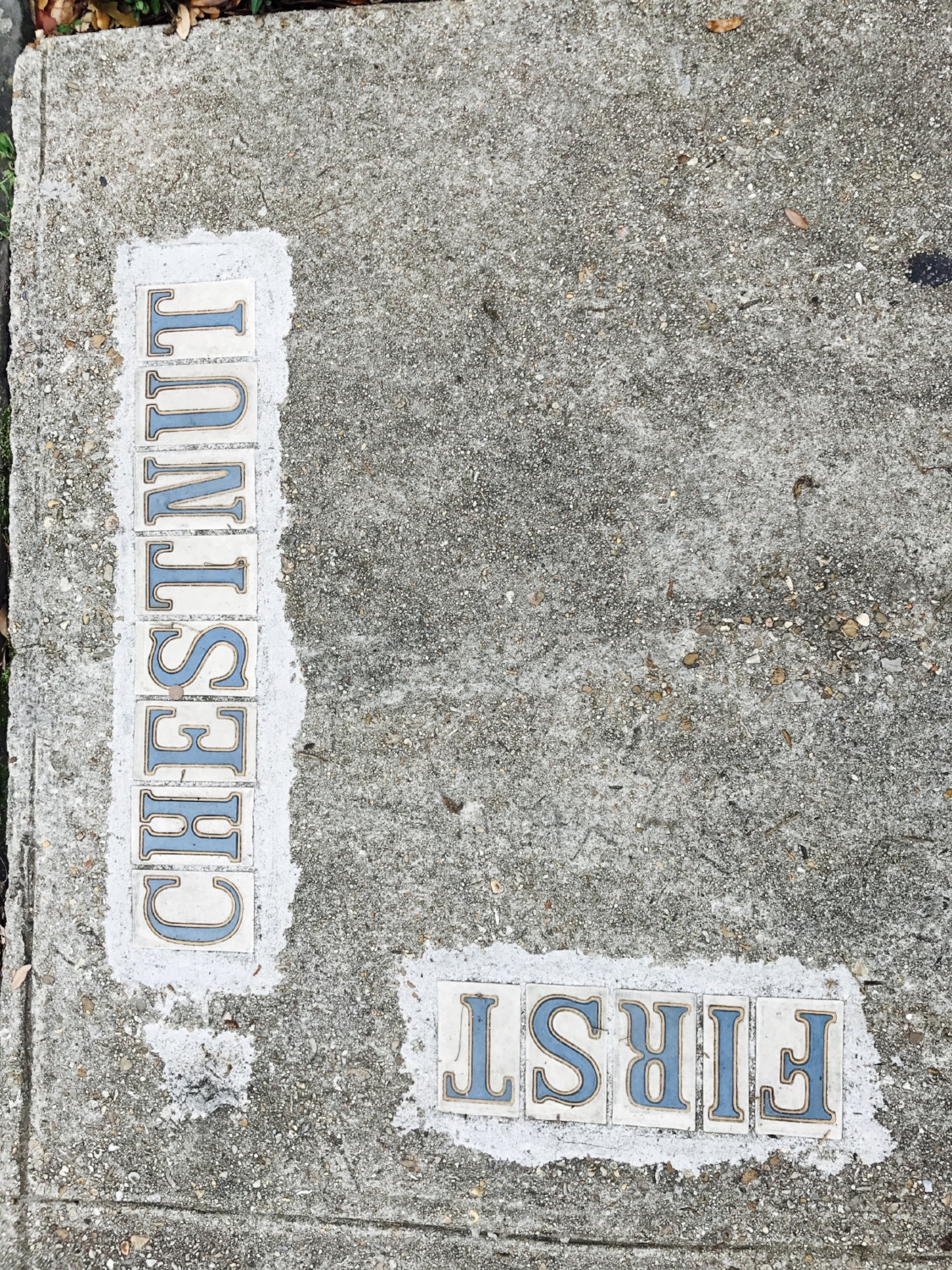

We ventured off constantly, veering directions we hadn't intended to go. We stayed up late wandering New Orleans, riding the streetcar through the Garden District for ice cream or into the French Quarter for midnight beignets at Café du Monde. We sat in cafes and restaurants, discussing our novels and sharing dessert. We sat in the van and drove slowly, begging the alligators to make one sly appearance. We shared the cultural experiences that Southern Louisiana had to offer, including the food, the festivities, and more food. We walked into a restaurant, a few minutes before it was closing, and ordered Chris his first drink to celebrate his 21st birthday. We had quickly become a close-knit group, constantly looking to each other as much as we looked to our books. And although we came from a similar basis in the English department, within our new environment, we were all stimulated to explore new angles.

The rich environment of New Orleans and Southern Louisiana, provided an expansive lens of cultures and traditions that welcomed an elaborate diversity into our thoughts. Our books allowed a deeper analysis into the histories and stories of the area, delving deeper into literary classics – cult or otherwise – that found their place in literary honors.

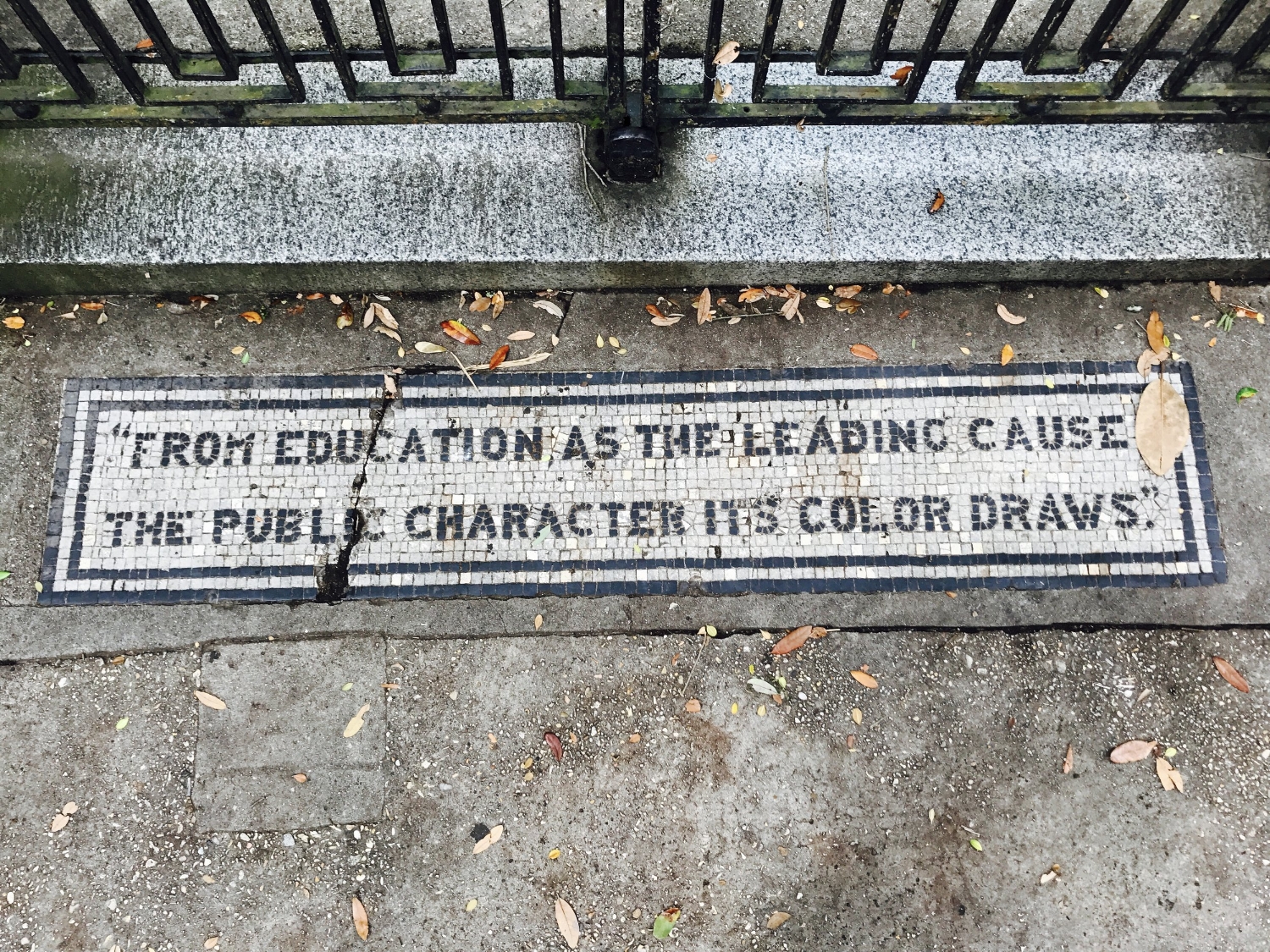

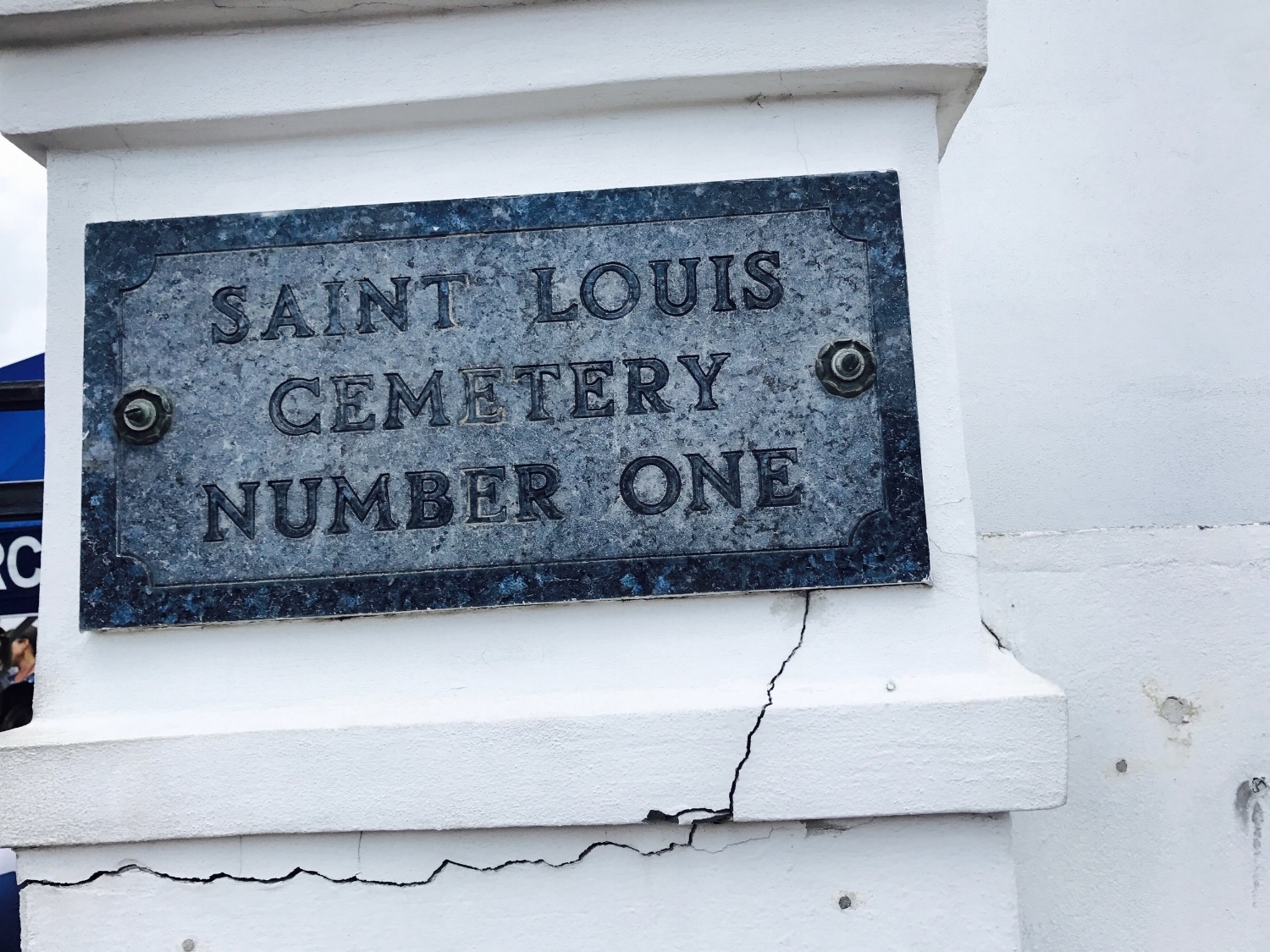

We felt somber as followed Kate Chopin to Grand Isle, and imagined Edna Pontellier running into the surf. We felt chills as we followed Anne Rice into the cemeteries, imagining Louis and Lestat having another epic argument over righteousness. We laughed loudly as we followed John Kennedy Toole through the French Quarter, and imagined Ignatious stuffing his face at his hotdog cart. We enjoyed our own existential crises as we followed Walker Percy into the Garden District, imagining Binx on an existential walk of his own. We followed quietly behind Robert Penn Warren into the capitol building in Baton Rouge, and imagined Willie Stark causing a scene. We sang along to country songs as we followed Tim Gautreaux into Cajun Country, imagining Floyd's race down the highway to save his little girl. And we quite literally followed Ernest J. Gaines into his home, imaging life for Grant and Jefferson on those sugar plantations. Bookpacking took us on an unforgettable adventure, leading us anywhere, and we followed.

“I can’t get no gator-action, I can’t get no gator-action. ‘Cause I try and I try and I try and I try.

I can’t get no, I can’t get no.”