As a kid, I was known to my family as the bookworm. Each book, even the ones I never finished, carried a memory. Over time, I fell in love with the idea of translating culture through character. Now, at twenty years old, my childhood hobby has finally come into fruition.

At first, bookpacking was disorienting. When you are informed about the author’s biographical history, their mindset while writing the book, and its legacy after publication, it already feels like an information overload. The weight of all that knowledge comes to us at once, and we cannot decipher which little voice in our head to listen to. On top of this, paying visits to their homes and inspirational spots, it becomes overstimulating to take everything in while making careful observations to calculate how much has changed and what remains. The geography on a map collides with imaginations, and together, they lead to the discussions in our seminar.

Gradually adjusting to the discipline of bookpacking, I became more encouraged to draw connections between locations and plotlines, creating a bold map of the literary scene. Even with countless speculations, extrapolations, and often naive guesses, I still arrived at many surprisingly satisfying conclusions. In that way, every new book is not just a new journey. Combined with the context I already know and the literary impulses I already possess, it’s a continuation of every journey I’ve ever taken.

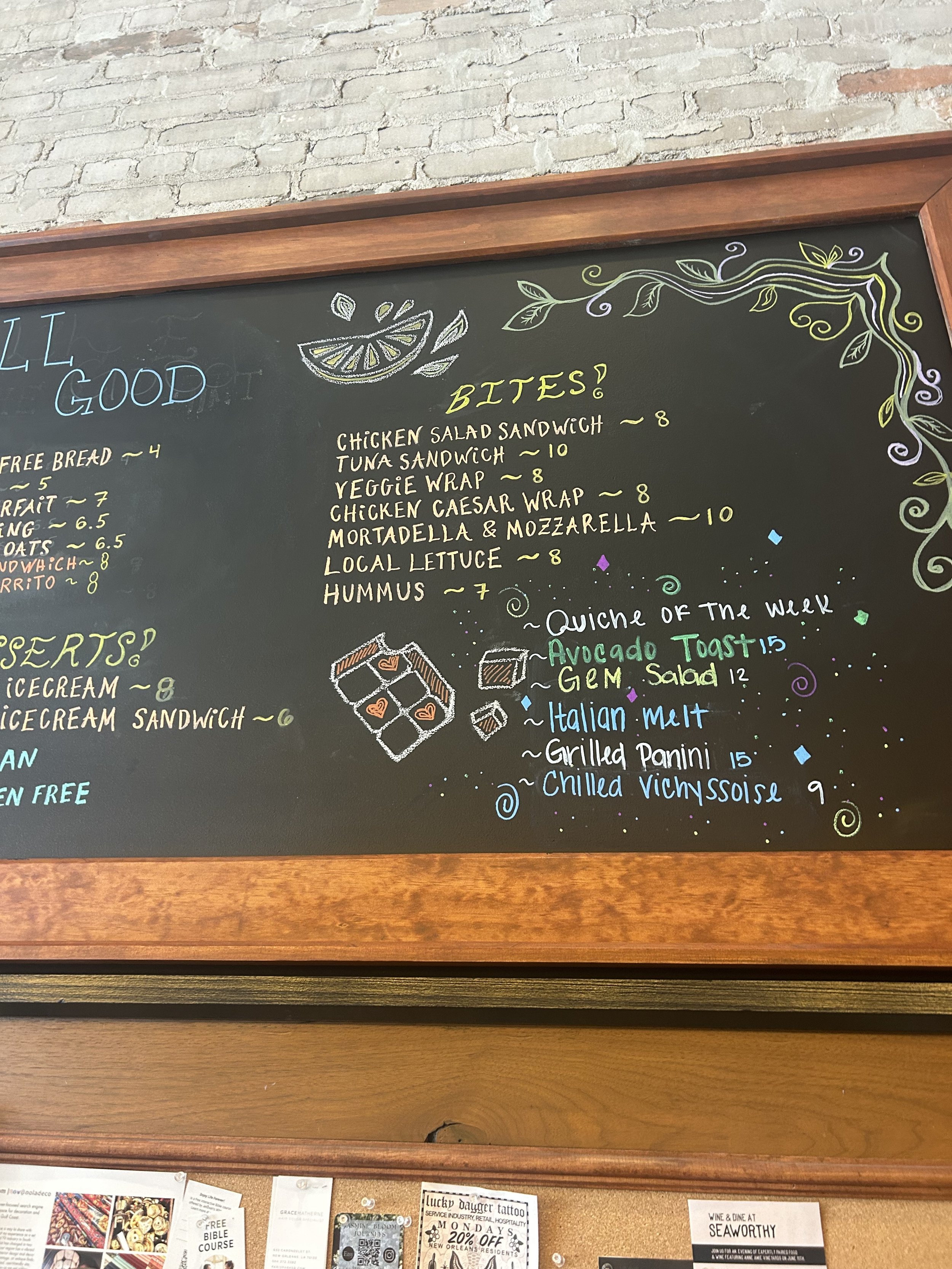

I used to be a stubborn student, insisting that I could only be productive if I focused with seriousness in a silent room, like the Doheny Library. However, bookpacking helped me let go of the uptight beliefs. Reading in motion—on the street car, sitting at the staircase leading to the Mississippi River, beside a street musician—all make the story porous. The real and the fictional bleed into each other.

The practice also taught me humility. Not every site I visited matched the grandeur of my expectations. Not every place felt sacred. Sometimes the house was torn down. New Orleans manages to move on faster than its people do. Standing where a story once happened, even if it's no longer recognizable, is a quiet act of mourning. When I read a story in the place where it was born, or where it’s set, I’m giving it my full presence and honoring the world it came from. And then there are the surprises. The places I stumbled into by accident, not because of a reading list, but because I was simply lost, early, or waiting for a bus. They left me with impressions that were stronger than I could have ever expected.

I may not always have the privilege of reading a multitude of books in the cities I stumble upon, but I can certainly be more intentional with my travels. From now on, deciding my itinerary will no longer revolve around the most popular landmarks and the locations with the highest reviews on TripAdvisor.

After this class, I learned that where you read a book matters almost as much as what you’re reading. I may never return to New Orleans again. Or maybe fate would lead me back to the familiar spots. Though it may be hard for me to find new reasons to come here, I also don’t have any valid excuses to reject a trip that takes me down memory lane. In fact, I plan on revisiting our catalog of books a couple of months or even a few years after our trip has commenced, so that I can be flooded with the previous active sensations. I am fortunate because reading allows me to revisit places I’ve loved without the expense of airfare.

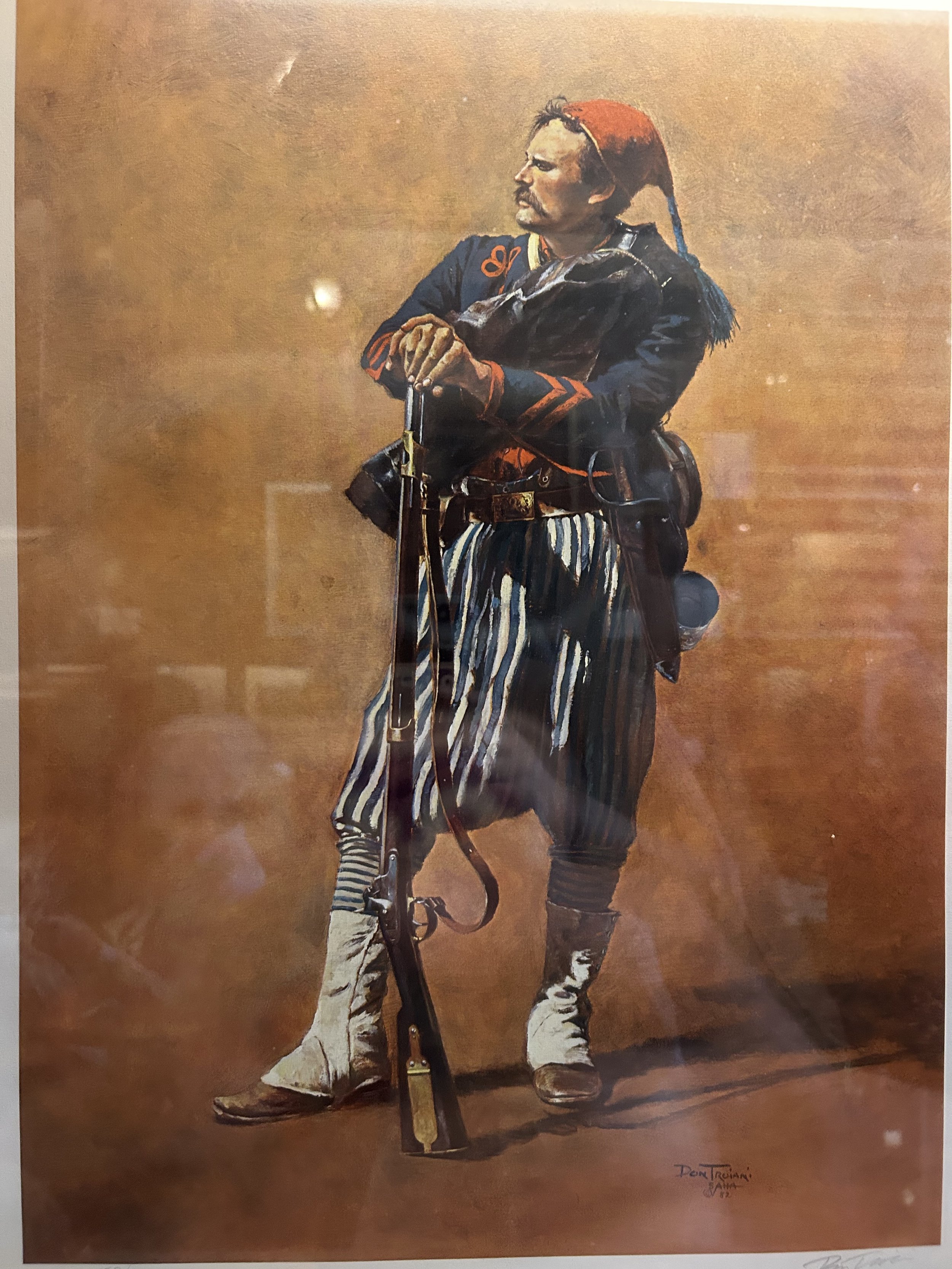

Although we never left the United States, the city was sometimes foreign to me. Our month-long adventures offered some strange gifts. After vigorously examining the decadent, licentious, mysterious attributes, we built our own versions of personal mythologies around places, making the departure bittersweet. These corners will live in a hidden spot in my frontal lobe: the shaded paths of Audubon Park, the sleepy façades in Gentilly, or the kaleidoscopic blur of Canal Street.

I plan to extend the traditions of bookpacking, introducing it to every aspect of my life, and continue this critical lens as I embrace more experiences. Whether it’s through art, food, or simple conversation, I want to situate myself as a temporary local in all the novel places. Within the country or across the world, I want to keep building my life this way and move slowly. I will be a reverent listener as much as I am a respectful reader, paying attention to the elements that typically slip through the tourists’ eyes.