London Train Station in the morning fog!

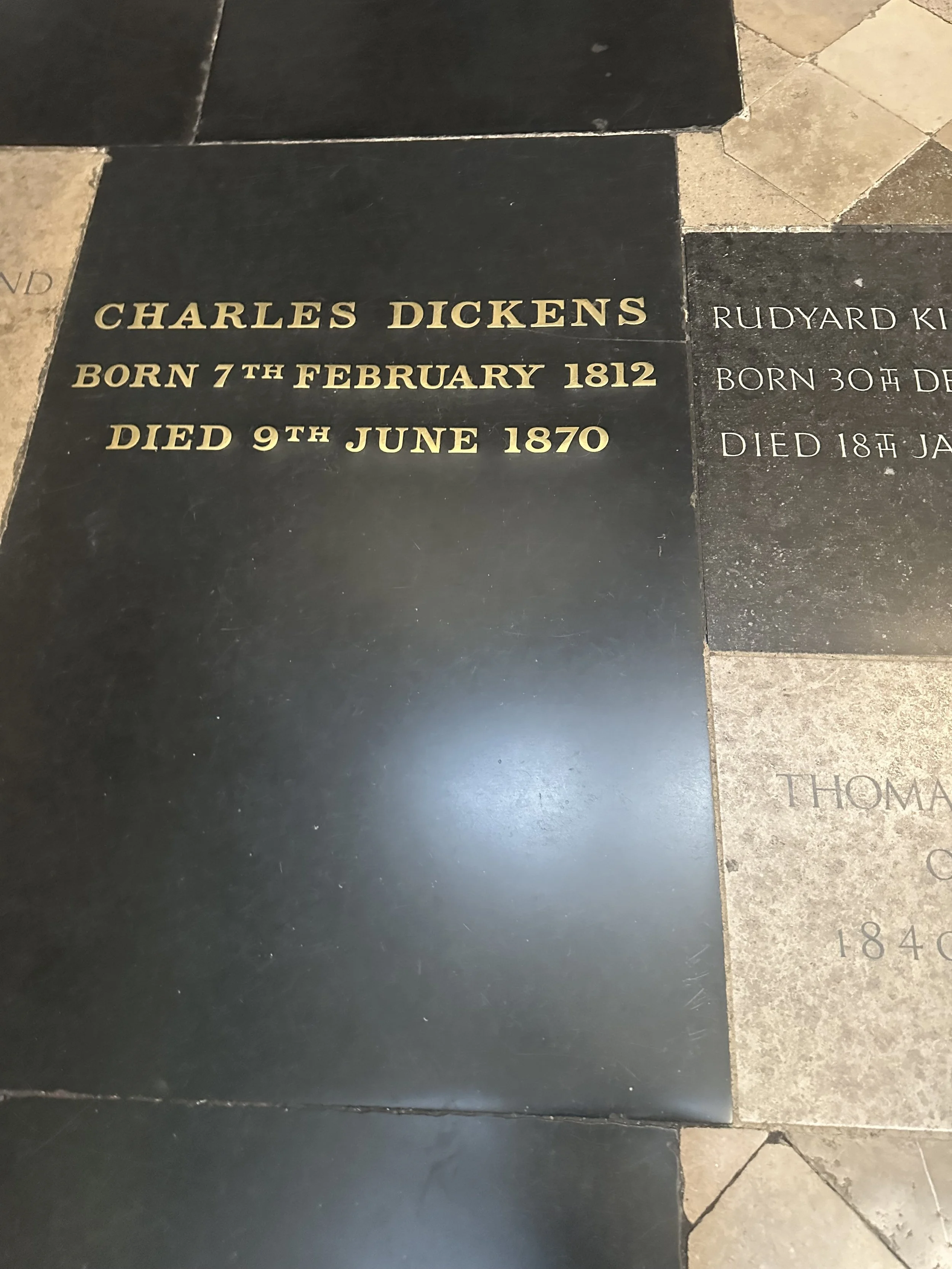

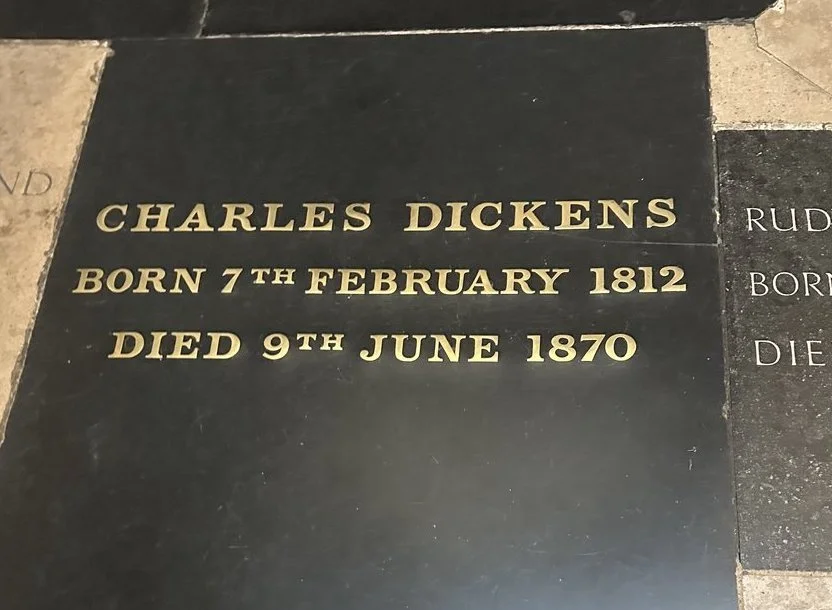

As it would happen, it was another Sunday. This Sunday, however, was different. It was 08:00 on a rainy monstrosity of a morning, and tensions were high as the members of our small class struggled to haul bags around and locate each other in the chaos of the bustling London train station. Eventually, and rather quickly, we gained our bearings and rendezvoused just in time to catch our morning train to Paris, our final destination. It felt like something out of the opening chapters of our Dickens novel A Tale of Two Cities. The same damp uneasiness of travel and thick fog of uncertainty hung in the air as we soon too would be the travelers in that dark Dover mail coach.

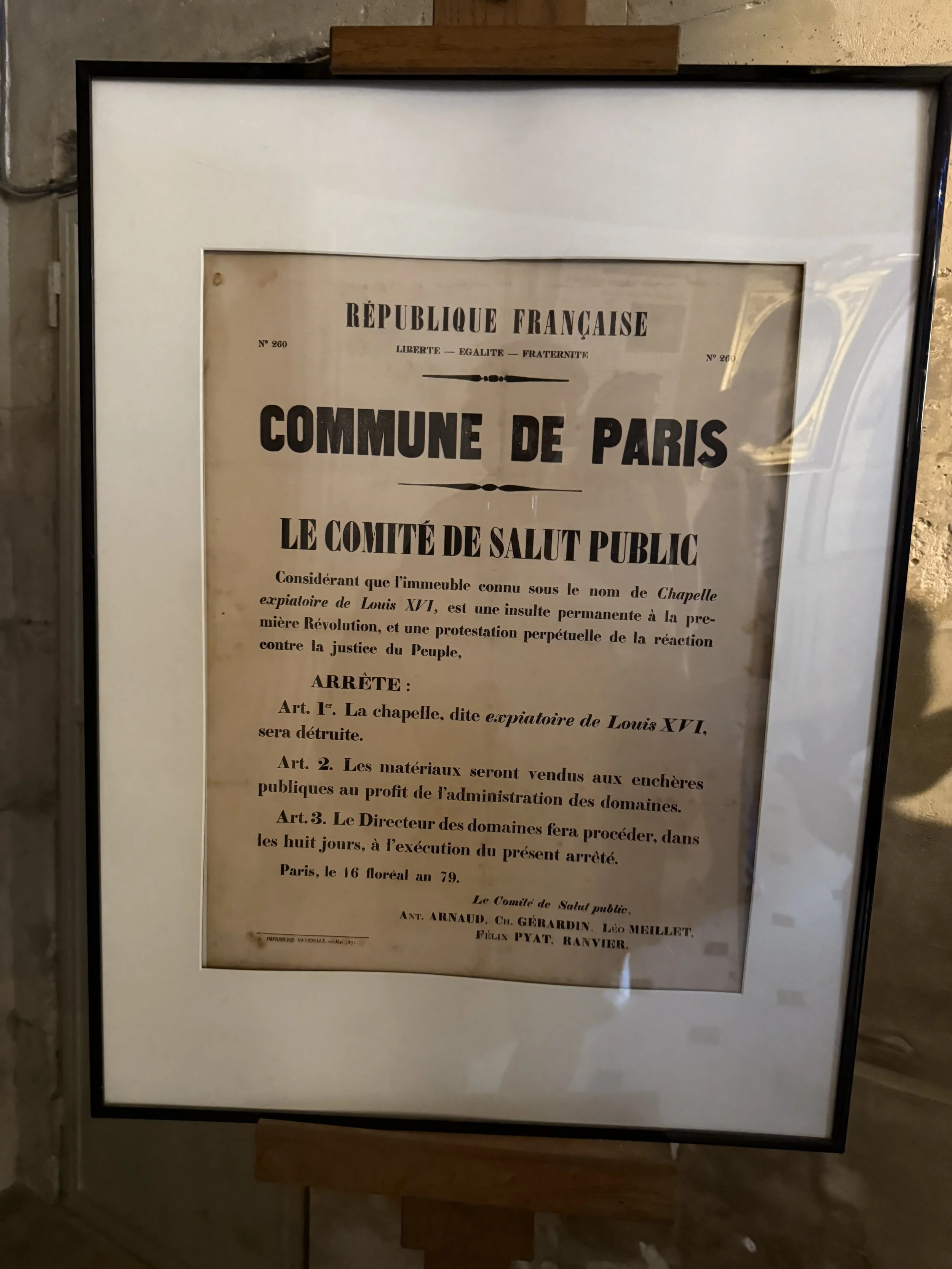

The entire class was antsy but excited for our main destination. Rightfully so. Not only is Paris a city of literary and historical significance (i.e. both of our books!), but it’s also the city of love and light, of dreams and midnight kisses, of cafés and conversation, of painters, poets, philosophy, style, secrets – and of course, revolution!

Although I’d been to Paris before during my post-service ex-patriate era (2023), I was just as eager to get back to her as everyone else was to discover her. After all, Paris is unequivocally my favorite city in the world. She’s like New York in the sense that every time you arrive you may as well arriving for the very first time. But this time was more special than most – I was excited to explore the dark corners of the city that Dickens so vividly described in the novel. From the site of the horrifying Bastille, to the intersection where the Defarges’ wine shop once stood (Rue de Sévigné & Rue de Rivoli), to the infamous Rue Saint-Honoré that once led straight to the guillotine.

Indeed for these reasons I was shocked to be stopped at the French customs and border patrol checkpoint still within the London train station. As I watched my classmates pass through without issue the officers decided it was worth it to hold me, of all people, at the border for some reason unbeknownst to me. As it would come out, they decided my passport was invalid as it was too close to its expiration date. French bureaucracy doing what it does best: wasting its goddamn time.

My emergency passport that would help me along the road

I was afforded the liberty to call my professor up, hoping he could use whatever French he had along with pure persuasion and pull some strings as a Dr. Manette sort of character. He returned from the train’s platform to meet me at the place they so rudely had me detained but, unfortunately, as they explained the issue to us both and I realized he would not have the same pull as the doctor did in the book. I shook his hand and sent him on his way back to the class with the departing words “I guess I’ll be seeing you in Paris tomorrow” The professor gave me a hopeful nod of agreement before the French officer took it upon himself to elaborate “No, you will not be entering France anytime soon!” After which we locked eyes again and he gave me an even more thorough nod, one that conveyed his exact thoughts: “Good luck, I know I can't stop you from trying.”

Fast forward eight hours and, with my emergency passport in hand (courtesy of the American Consulate in London), I was landing in Barcelona officially and in the EU. My new passport worked for most of the Schengen area, just not France. The objective was clear: enter mainland Europe legally and proceed to smuggle myself into France, legally. Should be easy enough, I’m half Mexican afterall… plus this was a border, and borders are meant to be crossed, right?

American Embassy in London

By 22:00 I was climbing aboard a red-eye bus headed to Paris. A fifteen-hour clandestine operation straight through a sleeping continent under the cover of night. If all went well I'd be enjoying a croque madame with my class by lunch. If the plan failed, It’d mean another unnecessary detention followed by a deportation straight back to the states. There was no margin for error. The Scheguen area is known for free trade and lax borders, but a quick search online showed that due to heightened tensions, notably Russias invasion of Ukaraine and Israels genocide in Gaza (Free Palestine!), France had indeed begun implementing 100% routine border checks.

Depiction of Darnay being questioned by revolutionaries

The bus was sleepy but I was not – every turn, every slowdown, every toll booth felt like they would be a border checkpoint and the end of the line for my impromptu adventure. One wrong turn and I would be left alone on the side of that dark road staring at the French border. One checkpoint and I would vanish from my class just as Dr. Monette had, swallowed by an indifferent system that offered no warning.

Somewhere between midnight and the Pyrenees and I recalled my trusty ally Darnay. When Darnay returns to France during the height of the French revolution (1792) he does so using his real name, hopeful that the authenticity of his purpose and the weight of his last name will protect him. Come to find out it doesn't, which scares me even more, since I only had half of such a compelling argument.

“Every town gate and village taxing-house had its band of citizen-patriots, with their national muskets in a most explosive state of readiness, who stopped all comers and goers, cross questioned them, inspected their papers, looked for their names in lists of their own, turned them back, or sent them on, or stopped them and laid them in hold, as their capricious judgment or fancy deemed best for the dawning Republic One and Indivisible, of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, or Death.”

I was in, and in deep. Once I was in Barcelona it certainly felt like there was no going back. If that wasn't the case, however, it was certainly true once I boarded the bus. Just as Darney, I could see those metaphoric iron doors closing behind me as I progressed on my unconventional journey towards Paris.

““Whatever might befall now, he must go on to his journey’s end. Not a mean village closed upon him, not a common barrier dropped across the road behind him, but he knew it to be another iron door in the series that was barred between him and England. The universal watchfulness so encompassed him, that if he had been taken in a net, or were being forwarded to his destination in a cage, he could not have felt his freedom more completely gone.”

”

A street sign I encountered in Orléans

Thankfully, I was much more lucky than my old friend Darnay. While he was arrested, and subsequently imprisoned, I had the luxury of dozing off on my bumpy ride before waking up near Orléans, just outside of Paris. A 15 hour bus ride is enough to drive any man mad, but I was lucky to get some sleep and not wake up in jail.

“They rested on some straw in a loft until the middle of the night, and then they rode forward again when all the town was asleep… Daylight at last found them before the wall of Paris”

By noon I was checking into my student lodging, and had just enough time to grab a quick bite before meeting my friends for the afternoon portion of our class – meaning that through the entire ordeal of (i)llegally sneaking into France I had only missed a single 2 hour lecture. Not bad at all. That afternoon we walked past the old site of La Forge, the very prison which Darnay is condemned to after his unsuccessful attempt of doing the exact same thing I did. As we left the site of the archaic institution I lit up a cigarette, and thought back to the French bureaucracy, and bureaucracy at large. How it wasted its time, since I still got in, and how most of them generally do the same. How such lifeless devotion to arbitrary rules and blind devotion to black and white systems rarely actually do what they're supposed to. I recalled the mindless guards in the book and, notably, Madame Defarge. Maybe sometimes rules are meant to be broken, I thought.

My own photo of the Tour Eiffel after a long but successful journey, shot on 35mm, Portra 400